At The Noyes House:

Blum & Poe, Mendes Wood DM and Object & Thing

September 15-November 28, 2020

New Canaan, CT

Photo by Michael Biondo

Use left/right arrows to navigate the slideshow or swipe left/right if using a mobile device

Object & Thing joined international contemporary art galleries, Blum & Poe and Mendes Wood DM , in presenting a collaborative exhibition of works of contemporary art and design in the domestic setting of Eliot Noyes’s (1910-1977) family home in New Canaan, Connecticut. The exhibition offered a unique opportunity for visitors to engage with the historic Modernist home of the industrial designer and Harvard Five architect. Taking the house and Noyes’s spirit as inspiration, At The Noyes House presented works by artists including Alma Allen, Lucas Arruda, Lynda Benglis, Sonia Gomes, Green River Project LLC, Mark Grotjahn, Kazunori Hamana, Jim McDowell, Antonio Obá and Faye Toogood among others. In addition to the organizing galleries, Object & Thing presented works contributed by art and design galleries: Ago Projects, Demisch Danant, Friedman Benda, Nonaka-Hill, Pace Gallery, Patrick Parrish Gallery, Salon 94 Design and Tiwa Select.

Installation Views

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Video Tour

A House in the Woods

Once upon a time, a black beast lived in a little house in the woods. It kept its back arched against the sky, all the better for children to crawl on it – for the beast was friendly, and stood very still. In the wintertime, snow would settle on its limbs, and it would look just right, with the walls gathered around it, walls of stone and walls of glass.

It sounds like something from a fairy tale, but it’s all true. The Black Beast II in question was a sculpture by Alexander Calder – a very early permanent “stabile,” executed in thick plates of steel. And the little house in the woods was, and is, a Modernist masterpiece by Eliot Noyes. Designed in 1954, completed in 1955, and beautifully preserved today, this was the second home that he built for himself and his family in New Canaan, Connecticut.

Noyes’s somewhat happenstance decision to move here paved the way for an influx of other architects in his circle – the so-called “Harvard Five,” among them Marcel Breuer and Philip Johnson, whose Glass House is only three and a half miles south. New Canaan became one of the main proving grounds for American Modernism, though not without local controversy. A poem that ran in the local paper took aim at Noyes and his allies, expressing the wish that they be confined in padded cells - “windowless, doorless, charmless, and escapeproof” - rather than unleash their frightening architecture on the innocent town.

It’s hard to imagine this sort of reaction nowadays. The shock of the new has worn away, leaving a deeper, abiding sense of wonder. The Noyes house is eminently livable, warm and intimate, entirely in harmony with its natural surroundings. Yet it is also a brilliant study in formal juxtaposition. In one direction, the walls are glass and steel, allowing for views right through the building and out to the landscape. In the other direction, the walls are made of local fieldstone. This axial contrast of transparency and opacity, of “International Style” and vernacular, infuses the house with remarkable energy, making it an extraordinary setting for art.

It’s in this spirit that an enterprising trio of organizations – the new-model fair Object & Thing, and the galleries Blum & Poe and Mendes Wood DM – are staging a gentle takeover of the house this fall. The building is 65 years old this year: retirement age. But as I write, it is taking on a new lease of life, as works of art and design once again fill the space. Eliot Noyes and his wife Molly were not collectors, exactly, but they sure knew how to orchestrate objects. Like their close friends Charles and Ray Eames out in California, they surrounded themselves with a creative mixture of fine art, folk craft, tapestries, African sculpture and Americana (notably including several carousel animals). As part of this collecting activity – described by Noyes as “a small, intermittent, economical operation but done with tremendous excitement by the whole family” – treated their living room table as a sort of exhibition-in-miniature, setting upon it small scale works by Calder, Joan Miró, Pablo Picasso and others. For anyone that associates Modernist display with white-walled galleries and strict disciplinary hierarchies, their characterful, ecumenical approach will come as a surprise.

Many of the artworks that the Noyes family brought here are now in other homes, or in museums; but this has led to the happy opportunity to repopulate it, in an equally ecumenical spirit. Where Black Beast II used to stand (Noyes bequeathed the sculpture to the collection at The Museum of Modern Art, where he had himself been a curator in the 1940s), a commanding work by Alma Allen now takes pride of place. Also in the courtyard, where there was once a set of slatted outdoor furniture, one can sit in a newly-made suite by Green River Project LLC; the corners of the enclosure are punctuated with large-scale pots by Kazunori Hamana. The living room table is again activated by a range of objects, including a not-so-miniature ceramic by Lynda Benglis and two face jugs by Jim McDowell, made in the southern African American tradition, and charged with contemporary relevance. Where another Calder – this one a mobile – used to hang, a fiber sculpture by Sonia Gomes clambers down from the ceiling in mid-air.

Several of the participating artists have created works especially for the exhibition, including Mark Grotjahn - who broke with his usual format, creating a horizontal painting to hang right above the hearth – and Daniel Steegmann Mangrané, whose aluminum ‘curtain’ reframes the view of the forest, rearticulating the porous boundary between outdoors and in. Sometimes you have to stop yourself and wonder. How long has that Sheila Hicks been hanging inside the door? What about that gorgeous boro textile on the bed, by Megumi Arai, or the subtle wood-fired ceramics of Frances Palmer? They’ve all only been here for a few days, as it turns out, but they feel right at home.

Curiously, something a little bit like this actually happened once before, when the house was brand new. In 1956 the Wadsworth Atheneum, in nearby Hartford, lent a houseful of American antiques to Noyes for the purposes of a Look magazine shoot. Eames chairs yielded their spots to ladderbacks. The family was photographed playing cards on a big hooked rug. The moral of the story, as far as Look was concerned, was that the “the battle between ‘traditional’ and ‘modern’ is over.”

Whether that was quite true at the time is questionable. But all these decades later, we do seem to be liberated from that either-or mentality. And that owes at least something to Noyes. He was a path-breaking figure in many ways: as a curator in the 1940s, he established the design program at MoMA, shaping it into an outpost for progressive and democratic thinking; as an architect in the 1950s, he played pied piper, turning New Canaan into a Modernist mecca; as a consultant to industry in the 1960s, he popularized the notion of universal design, preaching to his clients (among them IBM and Mobil) the virtue of consistency in all things – architecture, graphics and products.

As visitors flock to his house this fall, taking photos on their iPhones, they might well reflect that companies like Apple are essentially following the Noyes playbook. And to the extent that we’re all able to appreciate a Modernist chair, an abstract painting and a carousel giraffe all at once, we are also following in Eliot Noyes’s footsteps. As an innovator, his influence was both wide and deep. We can see it everywhere. But it is here, at his home, that we can experience his vision in its purest, holistic and accommodating form. In 1958, Noyes commented that aesthetic objects can “best be enjoyed in a house designed to bring art and their daily lives into as close daily contact possible.” He created just such a place, and that sense of contact is still alive and well: a modern story, with a fairytale ending.

By Glenn Adamson, an independent writer and curator based in New York

Artists

Alma Allen

Megumi Arai

Lucas Arruda

Lynda Benglis

Sergio Camargo

Miho Dohi

Hugo França

Aaron Garber-Maikovska

Tomoo Gokita

Sonia Gomes

Green River Project LLC

Mark Grotjahn

Kazunori Hamana

Sheila Hicks

Yukiko Kuroda

Mimi Lauter

Patricia Leite

Pablo Limón

Philippe Malouin

Daniel Steegmann Mangrané

Tony Marsh

Jim McDowell

Yoshitomo Nara

Paulo Nazareth

Antonio Obá

Johnny Ortiz

Frances Palmer

Gaetano Pesce

Celso Renato

Arlene Shechet

Faye Toogood

Rubem Valentim

Daniel Valero

Masaomi Yasunaga

Selected Works Presented by Object & Thing

Large Bedspread, 2020

Boro textile with hand-dyed details in pink and green, found floral fabric and indigo tilling

72 x 72 inches

Contributed by Tiwa Select

Japanese boro textiles have been at center stage in New York this year, thanks to an exhibition at the Japan Society. Boro (meaning “rags” or “tatters”) technique is comparable to the celebrated quilts of the American South - which are also often made with salvaged textiles - but have a very different compositional sensibility, featuring collage-like overlays. Megumi Arai has brought this tradition into the 21st century incorporating her own naturally made dyes, as part of a multidisciplinary practice that also includes photography and performance. Her work at the Noyes House occupies seemingly domestic formats. One of her textiles serves as the cover for a low-to-the-ground bed; another lies over the back of the living room sofa, in place of a Noyes family blanket. These gestures are humble, yet Arai’s works are also arresting abstractions, with individual patches floating atop one another to create a dynamic visual field.

Small Sofa Throw, 2020

Boro textile with hand-dyed details in pink and green, found floral fabric and indigo tilling

24 x 24 inches

Contributed by Tiwa Select

Japanese boro textiles have been at center stage in New York this year, thanks to an exhibition at the Japan Society. Boro (meaning “rags” or “tatters”) technique is comparable to the celebrated quilts of the American South - which are also often made with salvaged textiles - but have a very different compositional sensibility, featuring collage-like overlays. Megumi Arai has brought this tradition into the 21st century incorporating her own naturally made dyes, as part of a multidisciplinary practice that also includes photography and performance. Her work at the Noyes House occupies seemingly domestic formats. One of her textiles serves as the cover for a low-to-the-ground bed; another lies over the back of the living room sofa, in place of a Noyes family blanket. These gestures are humble, yet Arai’s works are also arresting abstractions, with individual patches floating atop one another to create a dynamic visual field.

Courtesy of Nonaka-Hill, Los Angeles

buttai 46, 2018

Wood, brass, paper, cloth and plaster

14 x 17 x 15 3/4 inches

Contributed by Nonaka-Hill

Buttai simply means “object” in Japanese; perhaps no more specific title would do for the works of the Kanazawa-based artist Miho Dohi. The small-scale assemblages that she makes – rarely more than a foot in any dimension – abide by no obvious rule of construction. They incorporate both natural and industrial materials, sometimes new and sometimes scavenged. Her works do not even resemble one another, necessarily, yet somehow always express the artist’s distinctive sensibility and intense curiosity, conveyed through dexterous compositions and a deep sensitivity to coloristic textural effects. Ultimately mysterious in their intention, illogical in the best sense of the term, they nonetheless feel just right – a perception the artist herself shares: “just when it seems to become clear what is inside and what is outside,” she has said, “they turn completely upside down, and all of a sudden, an object appears quite naturally out of that chaos.”

Photo by Sherry Griffin

Rings, 2007

Pequi wood

Small: Up to 23 5/8 inches in diameter

Medium: Between 24 and 33 1/2 inches in diameter

Large: Over 33 7/8 inches in diameter

Like Eliot Noyes, Hugo França was once an industrial designer – but look at him now. Departing his first profession to live in isolation in Bahia, in northeastern Brazil, in the early 1980s, he plunged into a deep and abiding relationship with nature, learning to work wood expressively at monumental size. His motivations were in part to do with environmental awareness, as he was saddened by the tragic waste of the timber extraction industry, and determined to give the felled trees new life. After fifteen years he returned to São Paulo to set up a studio, but his heart is still out there, in the rainforest. He has made furniture and pure sculpture, as well as many objects that hover somewhat ambiguously between those two categories; At The Noyes House includes one such inventive work, a group of rings made from a single root system. Like a giant’s toy, the objects can be stacked or leaned into any desired configuration, echoing at grand scale the interest that Modernists of Noyes’s generation (notably his friends Charles and Ray Eames) had in abstract play.

Photo by André Godoy

Guasca V Stool, 2017

Pequi wood

24 x 18 1/8 x 15 inches

Like Eliot Noyes, Hugo França was once an industrial designer – but look at him now. Departing his first profession to live in isolation in Bahia, in northeastern Brazil, in the early 1980s, he plunged into a deep and abiding relationship with nature, learning to work wood expressively at monumental size. His motivations were in part to do with environmental awareness, as he was saddened by the tragic waste of the timber extraction industry, and determined to give the felled trees new life. After fifteen years he returned to São Paulo to set up a studio, but his heart is still out there, in the rainforest. He has made furniture and pure sculpture, as well as many objects that hover somewhat ambiguously between those two categories; At The Noyes House includes one such inventive work, a group of rings made from a single root system. Like a giant’s toy, the objects can be stacked or leaned into any desired configuration, echoing at grand scale the interest that Modernists of Noyes’s generation (notably his friends Charles and Ray Eames) had in abstract play.

Pair of Pine-Board Deck Chairs, 2020

Clear pine and marine paint

27 x 30 1/2 x 36 inches each

Look at archival pictures of the Noyes House, and you will see a simple, slatted set of outdoor furniture in the courtyard, catty-corner to Calder’s Black Beast II. When preparing At the Noyes House, it made all the sense in the world to put a new suite in its place. Green River Project LLC took on the challenge. Founded in 2017 by Aaron Aujla and Benjamin Bloomstein, this New York City workshop is research-driven, both in its material selection and in its relationship to Modernist precedent – with an emphasis on creative recycling on both counts. Their Noyes House set may call to mind the Z-form chairs of the Dutch avant-garde master Gerrit Rietveld (a frequent reference for them); the material is the same one he sometimes used, common pine, in this case given gravitas through a subtle shiny finish. As to the table in the center, it is more in the mode of the French autodidact Alexandre Noll, ample in its proportions, with pairs of dowels protruding above each leg, a striking detail that draws attention to the massive joinery of the design. Elsewhere in the house, their Airline Pendant (actually made from found airplane parts) hangs where Noyes once had a lamp; their ebony ashtrays grace many of the house’s side tables, and their very first carved stone vessel can also be found. Making such simple objects so memorable is definitely not easy; arguably, the most impressive thing about Aujla and Bloomstein’s work is that they make it seem so.

Pine Outdoor Coffee Table, 2020

Reclaimed pine and marine paint

39 1/4 (diameter) x 16 1/2 inches

Look at archival pictures of the Noyes House, and you will see a simple, slatted set of outdoor furniture in the courtyard, catty-corner to Calder’s Black Beast II. When preparing At the Noyes House, it made all the sense in the world to put a new suite in its place. Green River Project LLC took on the challenge. Founded in 2017 by Aaron Aujla and Benjamin Bloomstein, this New York City workshop is research-driven, both in its material selection and in its relationship to Modernist precedent – with an emphasis on creative recycling on both counts. Their Noyes House set may call to mind the Z-form chairs of the Dutch avant-garde master Gerrit Rietveld (a frequent reference for them); the material is the same one he sometimes used, common pine, in this case given gravitas through a subtle shiny finish. As to the table in the center, it is more in the mode of the French autodidact Alexandre Noll, ample in its proportions, with pairs of dowels protruding above each leg, a striking detail that draws attention to the massive joinery of the design. Elsewhere in the house, their Airline Pendant (actually made from found airplane parts) hangs where Noyes once had a lamp; their ebony ashtrays grace many of the house’s side tables, and their very first carved stone vessel can also be found. Making such simple objects so memorable is definitely not easy; arguably, the most impressive thing about Aujla and Bloomstein’s work is that they make it seem so.

Ebony Ashtray, 2020

Ebony and boiled linseed oil

1 x 4 1/4 x 4 1/2 inches

Look at archival pictures of the Noyes House, and you will see a simple, slatted set of outdoor furniture in the courtyard, catty-corner to Calder’s Black Beast II. When preparing At the Noyes House, it made all the sense in the world to put a new suite in its place. Green River Project LLC took on the challenge. Founded in 2017 by Aaron Aujla and Benjamin Bloomstein, this New York City workshop is research-driven, both in its material selection and in its relationship to Modernist precedent – with an emphasis on creative recycling on both counts. Their Noyes House set may call to mind the Z-form chairs of the Dutch avant-garde master Gerrit Rietveld (a frequent reference for them); the material is the same one he sometimes used, common pine, in this case given gravitas through a subtle shiny finish. As to the table in the center, it is more in the mode of the French autodidact Alexandre Noll, ample in its proportions, with pairs of dowels protruding above each leg, a striking detail that draws attention to the massive joinery of the design. Elsewhere in the house, their Airline Pendant (actually made from found airplane parts) hangs where Noyes once had a lamp; their ebony ashtrays grace many of the house’s side tables, and their very first carved stone vessel can also be found. Making such simple objects so memorable is definitely not easy; arguably, the most impressive thing about Aujla and Bloomstein’s work is that they make it seem so.

Stone Vessel, 2020

Limestone

3 x 12 x 10 inches

Look at archival pictures of the Noyes House, and you will see a simple, slatted set of outdoor furniture in the courtyard, catty-corner to Calder’s Black Beast II. When preparing At the Noyes House, it made all the sense in the world to put a new suite in its place. Green River Project LLC took on the challenge. Founded in 2017 by Aaron Aujla and Benjamin Bloomstein, this New York City workshop is research-driven, both in its material selection and in its relationship to Modernist precedent – with an emphasis on creative recycling on both counts. Their Noyes House set may call to mind the Z-form chairs of the Dutch avant-garde master Gerrit Rietveld (a frequent reference for them); the material is the same one he sometimes used, common pine, in this case given gravitas through a subtle shiny finish. As to the table in the center, it is more in the mode of the French autodidact Alexandre Noll, ample in its proportions, with pairs of dowels protruding above each leg, a striking detail that draws attention to the massive joinery of the design. Elsewhere in the house, their Airline Pendant (actually made from found airplane parts) hangs where Noyes once had a lamp; their ebony ashtrays grace many of the house’s side tables, and their very first carved stone vessel can also be found. Making such simple objects so memorable is definitely not easy; arguably, the most impressive thing about Aujla and Bloomstein’s work is that they make it seem so.

Airline Pendant, 2020

Found airline parts and electrical components

11 x 28 x 10 inches; Length of cord is 64 inches

Look at archival pictures of the Noyes House, and you will see a simple, slatted set of outdoor furniture in the courtyard, catty-corner to Calder’s Black Beast II. When preparing At the Noyes House, it made all the sense in the world to put a new suite in its place. Green River Project LLC took on the challenge. Founded in 2017 by Aaron Aujla and Benjamin Bloomstein, this New York City workshop is research-driven, both in its material selection and in its relationship to Modernist precedent – with an emphasis on creative recycling on both counts. Their Noyes House set may call to mind the Z-form chairs of the Dutch avant-garde master Gerrit Rietveld (a frequent reference for them); the material is the same one he sometimes used, common pine, in this case given gravitas through a subtle shiny finish. As to the table in the center, it is more in the mode of the French autodidact Alexandre Noll, ample in its proportions, with pairs of dowels protruding above each leg, a striking detail that draws attention to the massive joinery of the design. Elsewhere in the house, their Airline Pendant (actually made from found airplane parts) hangs where Noyes once had a lamp; their ebony ashtrays grace many of the house’s side tables, and their very first carved stone vessel can also be found. Making such simple objects so memorable is definitely not easy; arguably, the most impressive thing about Aujla and Bloomstein’s work is that they make it seem so.

© Kazunori Hamana, Courtesy of the artist, Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo, and Object & Thing Photo: Makenzie Goodman

Untitled, 2019

Ceramic

35 1/2 x 41 x 38 3/4 inches

Contributed by Blum & Poe

Ready to be impressed? Have a look at the astonishing vessels of Kazunori Hamana, which sit in the Noyes House courtyard like ancient monuments long adrift that have somehow come to rest. Built by hand using a variety of natural clays, sourced from Shiga prefecture in Japan, each is finished with Hamana’s own mineral glazes. In their scale, they seem almost to rival the natural environment from which he has so skillfully wrested them. But they are of course deeply cultural, making conscious reference to the traditional Japanese tsubo, a functional clay jar dating back to prehistoric times, used to store and process food. A distinctive aspect of Hamana’s practice is the ageing of his great pots. Once fired, the works are placed outside and around his studio on the east coast of Japan where they are left to accumulate a surface with the changing of the seasons.

© Kazunori Hamana, Courtesy of the artist, Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo, and Object & Thing Photo: Makenzie Goodman

Untitled, 2019

Ceramic

37 5/8 x 40 3/4 x 38 inches

Contributed by Blum & Poe

Ready to be impressed? Have a look at the astonishing vessels of Kazunori Hamana, which sit in the Noyes House courtyard like ancient monuments long adrift that have somehow come to rest. Built by hand using a variety of natural clays, sourced from Shiga prefecture in Japan, each is finished with Hamana’s own mineral glazes. In their scale, they seem almost to rival the natural environment from which he has so skillfully wrested them. But they are of course deeply cultural, making conscious reference to the traditional Japanese tsubo, a functional clay jar dating back to prehistoric times, used to store and process food. A distinctive aspect of Hamana’s practice is the ageing of his great pots. Once fired, the works are placed outside and around his studio on the east coast of Japan where they are left to accumulate a surface with the changing of the seasons.

© Kazunori Hamana and © Yukiko Kuroda, Courtesy of the artists, Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo, and Object & Thing

Untitled, 2019

Ceramic

25 1/2 x 28 3/4 x 25 inches

Contributed by Blum & Poe

Ready to be impressed? Have a look at the astonishing vessels of Kazunori Hamana, which sit in the Noyes House courtyard like ancient monuments long adrift that have somehow come to rest. Built by hand using a variety of natural clays, sourced from Shiga prefecture in Japan, each is finished with Hamana’s own mineral glazes. In their scale, they seem almost to rival the natural environment from which he has so skillfully wrested them. But they are of course deeply cultural, making conscious reference to the traditional Japanese tsubo, a functional clay jar dating back to prehistoric times, used to store and process food. A distinctive aspect of Hamana’s practice is the ageing of his great pots. Once fired, the works are placed outside and around his studio on the east coast of Japan where they are left to accumulate a surface with the changing of the seasons.

Hamana collaborates with fellow Chiba-based artist Yukiko Kuroda on vessels that he considers damaged or otherwise imperfect. Kuroda accentuating the imperfections of these works, sometimes adding Japanese lacquer and polishing powder – her interpretation of the celebrated Japanese custom of kintsugi – or by adjoining flaking or cast-off layers of ceramics from other vessels, which are created organically during the pottery process. Despite the much smaller scale of these interventions, the process often takes longer than the time it takes Hamana to create the pot itself.

Courtesy of Demisch Danant

Prayer Rug, 1978

Wool

56 3/8 x 20 1/2 inches

Contributed by Demisch Danant

The great Sheila Hicks presides over the story of fiber art like a queen of old – though she has never been much interested in holding court. She is an inveterate and curious traveler, much affected by her time in Mexico and elsewhere in Latin America, in India, and in Paris, where she now lives and works, among many other parts of the world. Hicks is also a deep student of fiber forms, and it is perhaps unsurprising – given her global view of the subject – that at some point, her eagle eye would have lit upon the prayer rug. One cannot imagine a more spiritually charged textile genre, though she typically made it her own, while respecting the cultural source. The example shown at the Noyes House, from 1978 - a nod to the tapestries by artists such as Henri Matisse and Joan Miró which once were here - adapts the rough composition of a traditional prayer rug. These typically feature arches, evoking the architecture of a mosque, and are laid out with the motif pointing to Mecca, in the direction of worship. Hung vertically on the wall, Hicks’s work suggests a broader narrative about spiritual elevation, while also recalling abstract painting, which was her first métier, when she studied at Yale with Josef Albers – not too far from New Canaan.

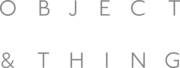

Silver Nitrates - Prototype #2, 2019

Foam, silver nitrate

18 x 17 x 17 inches

Contributed by Patrick Parrish Gallery

“Today, luxury is not perceived as it once was,” Pablo Limón has said. “We experience two luxuries that do not speak the same language and do not live within the same values.” His own work crosses this divide, hybridizing a relatively orthodox vocabulary of modern design (often featuring planar functional forms) with a street sensibility. The seating furniture he is showing at the Noyes House is from a recent series created in collaboration with the DS Paint workshop in Barcelona. It consists of planar constructions of hard foam, which are surfaced in silver nitrate and dyes, and chromed with a chemical catalyst. The process is repeated across several layers, and then selectively buffed with a circular sander. The result is a polychromatic, reflective surface – very unearthly in effect, like something out of science fiction – but in practice the process is quite painterly, allowing Limón a wide range of graphic possibilities.

Silver Nitrates - Prototype #3, 2019

Foam, silver nitrate

18 x 17 x 17 inches

Contributed by Patrick Parrish Gallery

“Today, luxury is not perceived as it once was,” Pablo Limón has said. “We experience two luxuries that do not speak the same language and do not live within the same values.” His own work crosses this divide, hybridizing a relatively orthodox vocabulary of modern design (often featuring planar functional forms) with a street sensibility. The seating furniture he is showing at the Noyes House is from a recent series created in collaboration with the DS Paint workshop in Barcelona. It consists of planar constructions of hard foam, which are surfaced in silver nitrate and dyes, and chromed with a chemical catalyst. The process is repeated across several layers, and then selectively buffed with a circular sander. The result is a polychromatic, reflective surface – very unearthly in effect, like something out of science fiction – but in practice the process is quite painterly, allowing Limón a wide range of graphic possibilities.

Telephone, 2019

Nylon

7 x 10 1/4 x 6 1/2 inches

Contributed by Salon 94 Design

Of all the curatorial moments in At the Noyes House, perhaps the most delicious is the juxtaposition of the designer’s Selectrix IBM typewriter – the most famous of his industrial products – with Philippe Malouin’s blue nylon telephone. This blind date between the two objects is a fascinating study in similarities and differences. Most obviously, Malouin’s functional landline alludes back to midcentury technology; the French designer created it as part of a suite entitled Industrial Office, which updated various Modernist forms in colorful nylon and simplified lines, to uncanny effect. It’s as if one’s mental image of a phone had somehow manifested itself in real space, or conversely, as if we were somehow inhabiting a comic book narrative, complete with props. This playful, “meta” quality announces a postmodern viewpoint completely at odds with the earnest functionalism of Noyes’s typewriter. Yet, beyond this difference, there is an underlying commonality. Both objects are honed to their absolute essence, achieving an unforgettable charisma. It just goes to show that as much as design has changed over the decades, some of what makes an object great is the same as ever.

Ice Cauldron, 2020

Glazed ceramic

14 1/2 x 9 x 8 1/2 inches

Contributed by Ago Projects

The eminent ceramist and educator Tony Marsh works in several discrete idioms, typically focusing his attention on the vessel form. One of his series is cleanly modeled, white, and perforated; another takes the form of low bowl forms, brimming with curious handmade objects; still another interprets the idea of containment in a more rectilinear fashion, with connections to architecture. The object included at the Noyes House is different from all of these. Sheathed in a spectacular blue glaze with crystalline accretions, it feels geologically extracted rather than hand-built. It is part of his Cauldron series – a term that could equally suggest a volcanic caldera or a witch’s brew, and are equally apt associations for the object.

Madison Washington, 2017

Ceramic fired in a gas kiln with salt and soda, amber celadon glaze and glass runs

8 x 5 inches

Contributed by Tiwa Select

“I am not a folk artist although many have tried to put me into that category,” Jim McDowell has said. “I call myself the Black Potter.” With this matter-of-fact statement, McDowell takes ownership of his position in a long narrative of great artists – a few whose names are known today, the great majority anonymous. Face jugs of the kind he makes have been created in the American South and elsewhere in the African diaspora since at least the mid-nineteenth century. Research points to strong connections between this form and West African sculptural traditions, which were displaced here along with millions of enslaved people. McDowell’s work testifies to this terrible history, while also paying tribute to those artists who contested it – notably the famed David Drake (aka “Dave the Potter”), whose poetic inscriptions McDowell emulates on his own ceramics; and his own four-times-great aunt Evangeline, who was a potter and face jug maker in Jamaica.

In the context of the Noyes House, McDowell’s work takes on further critical force. It enacts a rupture in this placid, white, suburban milieu – the kind of neighborhood that very few Black Americans were able to inhabit in the postwar era, thanks to racist red-lining practices – and also casts a clarifying light on the African carvings and other “folk” objects that Eliot and Molly Noyes collected. This was an interest they shared with many other Modernists of their generation (Charles and Ray Eames, for example), who typically did little to preserve the specific cultural history of those artifacts. Yet it would be wrong to see McDowell’s work as only oppositional, in this context; it is also tremendously affirmative, emblematizing a realm of creativity that was too often obscured during the heyday of Modernism, and is now finally getting its proper respect. As McDowell reminds us: “My lineage was interrupted, but not lost.”

Two-Face, 2018

Ceramic fired in a gas kiln, rutile blue glaze

8 x 9 inches

Contributed by Tiwa Select

“I am not a folk artist although many have tried to put me into that category,” Jim McDowell has said. “I call myself the Black Potter.” With this matter-of-fact statement, McDowell takes ownership of his position in a long narrative of great artists – a few whose names are known today, the great majority anonymous. Face jugs of the kind he makes have been created in the American South and elsewhere in the African diaspora since at least the mid-nineteenth century. Research points to strong connections between this form and West African sculptural traditions, which were displaced here along with millions of enslaved people. McDowell’s work testifies to this terrible history, while also paying tribute to those artists who contested it – notably the famed David Drake (aka “Dave the Potter”), whose poetic inscriptions McDowell emulates on his own ceramics; and his own four-times-great aunt Evangeline, who was a potter and face jug maker in Jamaica.

In the context of the Noyes House, McDowell’s work takes on further critical force. It enacts a rupture in this placid, white, suburban milieu – the kind of neighborhood that very few Black Americans were able to inhabit in the postwar era, thanks to racist red-lining practices – and also casts a clarifying light on the African carvings and other “folk” objects that Eliot and Molly Noyes collected. This was an interest they shared with many other Modernists of their generation (Charles and Ray Eames, for example), who typically did little to preserve the specific cultural history of those artifacts. Yet it would be wrong to see McDowell’s work as only oppositional, in this context; it is also tremendously affirmative, emblematizing a realm of creativity that was too often obscured during the heyday of Modernism, and is now finally getting its proper respect. As McDowell reminds us: “My lineage was interrupted, but not lost.”

Warrior Queen, 2020

Ceramic fired in a gas kiln with salt and soda, sea foam glaze

8 x 9 inches

Contributed by Tiwa Select

“I am not a folk artist although many have tried to put me into that category,” Jim McDowell has said. “I call myself the Black Potter.” With this matter-of-fact statement, McDowell takes ownership of his position in a long narrative of great artists – a few whose names are known today, the great majority anonymous. Face jugs of the kind he makes have been created in the American South and elsewhere in the African diaspora since at least the mid-nineteenth century. Research points to strong connections between this form and West African sculptural traditions, which were displaced here along with millions of enslaved people. McDowell’s work testifies to this terrible history, while also paying tribute to those artists who contested it – notably the famed David Drake (aka “Dave the Potter”), whose poetic inscriptions McDowell emulates on his own ceramics; and his own four-times-great aunt Evangeline, who was a potter and face jug maker in Jamaica.

In the context of the Noyes House, McDowell’s work takes on further critical force. It enacts a rupture in this placid, white, suburban milieu – the kind of neighborhood that very few Black Americans were able to inhabit in the postwar era, thanks to racist red-lining practices – and also casts a clarifying light on the African carvings and other “folk” objects that Eliot and Molly Noyes collected. This was an interest they shared with many other Modernists of their generation (Charles and Ray Eames, for example), who typically did little to preserve the specific cultural history of those artifacts. Yet it would be wrong to see McDowell’s work as only oppositional, in this context; it is also tremendously affirmative, emblematizing a realm of creativity that was too often obscured during the heyday of Modernism, and is now finally getting its proper respect. As McDowell reminds us: “My lineage was interrupted, but not lost.”

Spike, 2015

Ceramic fired in a wood burning kiln, green mottled glaze

10 x 9 inches

Contributed by Tiwa Select

“I am not a folk artist although many have tried to put me into that category,” Jim McDowell has said. “I call myself the Black Potter.” With this matter-of-fact statement, McDowell takes ownership of his position in a long narrative of great artists – a few whose names are known today, the great majority anonymous. Face jugs of the kind he makes have been created in the American South and elsewhere in the African diaspora since at least the mid-nineteenth century. Research points to strong connections between this form and West African sculptural traditions, which were displaced here along with millions of enslaved people. McDowell’s work testifies to this terrible history, while also paying tribute to those artists who contested it – notably the famed David Drake (aka “Dave the Potter”), whose poetic inscriptions McDowell emulates on his own ceramics; and his own four-times-great aunt Evangeline, who was a potter and face jug maker in Jamaica.

In the context of the Noyes House, McDowell’s work takes on further critical force. It enacts a rupture in this placid, white, suburban milieu – the kind of neighborhood that very few Black Americans were able to inhabit in the postwar era, thanks to racist red-lining practices – and also casts a clarifying light on the African carvings and other “folk” objects that Eliot and Molly Noyes collected. This was an interest they shared with many other Modernists of their generation (Charles and Ray Eames, for example), who typically did little to preserve the specific cultural history of those artifacts. Yet it would be wrong to see McDowell’s work as only oppositional, in this context; it is also tremendously affirmative, emblematizing a realm of creativity that was too often obscured during the heyday of Modernism, and is now finally getting its proper respect. As McDowell reminds us: “My lineage was interrupted, but not lost.”

Love Trumps Hate, 2019

Ceramic fired in a gas kiln with salt and soda, Albany slip glaze, amber celadon glaze and glass runs

9 1/2 x 8 inches

Contributed by Tiwa Select

“I am not a folk artist although many have tried to put me into that category,” Jim McDowell has said. “I call myself the Black Potter.” With this matter-of-fact statement, McDowell takes ownership of his position in a long narrative of great artists – a few whose names are known today, the great majority anonymous. Face jugs of the kind he makes have been created in the American South and elsewhere in the African diaspora since at least the mid-nineteenth century. Research points to strong connections between this form and West African sculptural traditions, which were displaced here along with millions of enslaved people. McDowell’s work testifies to this terrible history, while also paying tribute to those artists who contested it – notably the famed David Drake (aka “Dave the Potter”), whose poetic inscriptions McDowell emulates on his own ceramics; and his own four-times-great aunt Evangeline, who was a potter and face jug maker in Jamaica.

In the context of the Noyes House, McDowell’s work takes on further critical force. It enacts a rupture in this placid, white, suburban milieu – the kind of neighborhood that very few Black Americans were able to inhabit in the postwar era, thanks to racist red-lining practices – and also casts a clarifying light on the African carvings and other “folk” objects that Eliot and Molly Noyes collected. This was an interest they shared with many other Modernists of their generation (Charles and Ray Eames, for example), who typically did little to preserve the specific cultural history of those artifacts. Yet it would be wrong to see McDowell’s work as only oppositional, in this context; it is also tremendously affirmative, emblematizing a realm of creativity that was too often obscured during the heyday of Modernism, and is now finally getting its proper respect. As McDowell reminds us: “My lineage was interrupted, but not lost.”

Tribal Chieftain, 2020

Ceramic fired in a gas kiln with salt and soda, amber celadon glaze and glass runs

10 1/2 x 8 inches

Contributed by Tiwa Select

“I am not a folk artist although many have tried to put me into that category,” Jim McDowell has said. “I call myself the Black Potter.” With this matter-of-fact statement, McDowell takes ownership of his position in a long narrative of great artists – a few whose names are known today, the great majority anonymous. Face jugs of the kind he makes have been created in the American South and elsewhere in the African diaspora since at least the mid-nineteenth century. Research points to strong connections between this form and West African sculptural traditions, which were displaced here along with millions of enslaved people. McDowell’s work testifies to this terrible history, while also paying tribute to those artists who contested it – notably the famed David Drake (aka “Dave the Potter”), whose poetic inscriptions McDowell emulates on his own ceramics; and his own four-times-great aunt Evangeline, who was a potter and face jug maker in Jamaica.

In the context of the Noyes House, McDowell’s work takes on further critical force. It enacts a rupture in this placid, white, suburban milieu – the kind of neighborhood that very few Black Americans were able to inhabit in the postwar era, thanks to racist red-lining practices – and also casts a clarifying light on the African carvings and other “folk” objects that Eliot and Molly Noyes collected. This was an interest they shared with many other Modernists of their generation (Charles and Ray Eames, for example), who typically did little to preserve the specific cultural history of those artifacts. Yet it would be wrong to see McDowell’s work as only oppositional, in this context; it is also tremendously affirmative, emblematizing a realm of creativity that was too often obscured during the heyday of Modernism, and is now finally getting its proper respect. As McDowell reminds us: “My lineage was interrupted, but not lost.”

Your Chains Can’t Hold Me, 2020

Ceramic fired in a gas kiln with salt and soda, glazed with amber celadon

10 1/2 x 11 inches

Contributed by Tiwa Select

“I am not a folk artist although many have tried to put me into that category,” Jim McDowell has said. “I call myself the Black Potter.” With this matter-of-fact statement, McDowell takes ownership of his position in a long narrative of great artists – a few whose names are known today, the great majority anonymous. Face jugs of the kind he makes have been created in the American South and elsewhere in the African diaspora since at least the mid-nineteenth century. Research points to strong connections between this form and West African sculptural traditions, which were displaced here along with millions of enslaved people. McDowell’s work testifies to this terrible history, while also paying tribute to those artists who contested it – notably the famed David Drake (aka “Dave the Potter”), whose poetic inscriptions McDowell emulates on his own ceramics; and his own four-times-great aunt Evangeline, who was a potter and face jug maker in Jamaica.

In the context of the Noyes House, McDowell’s work takes on further critical force. It enacts a rupture in this placid, white, suburban milieu – the kind of neighborhood that very few Black Americans were able to inhabit in the postwar era, thanks to racist red-lining practices – and also casts a clarifying light on the African carvings and other “folk” objects that Eliot and Molly Noyes collected. This was an interest they shared with many other Modernists of their generation (Charles and Ray Eames, for example), who typically did little to preserve the specific cultural history of those artifacts. Yet it would be wrong to see McDowell’s work as only oppositional, in this context; it is also tremendously affirmative, emblematizing a realm of creativity that was too often obscured during the heyday of Modernism, and is now finally getting its proper respect. As McDowell reminds us: “My lineage was interrupted, but not lost.”

Set of works: 1 platter, 1 large bowl, 1 medium bowl, 2020

Micaceous earth from Northern New Mexico, sanded with local sandstone,

burnished with a river stone, pit fired with red cedar, and cured with elk marrow and beeswax

Platter: 14 3/4 x 14 3/4 x 1 inches; Large bowl: 11 1/4 x 11 1/4 x 3 inches; Medium bowl: 7 1/4 x 7 1/4 x 2 1/2 inches

There’s clay, and then there’s clay. Johnny Ortiz is the founder of the pioneering New Mexico entity called Shed: an ambitious project incorporating an art and design studio and a restaurant, premised on intensely local ingredients in its every aspect. This holds true for the ceramics he is showing at the Noyes House. They are made of what Ortiz calls “wild clays,” foraged from the surrounding landscape. These same materials have been used by indigenous and Latina/Latino potters for centuries, and his continuation of the tradition shares some time-honored traits: an overall dark palette, with glimmers of light thanks to tiny fleck of mica held within the body. Riffing on precedent, Ortiz has developed a laborious and loving process: sanding the pots with sandstone, burnishing them with a river stone, pit firing with red mountain cedar, and curing with elk marrow and beeswax. Each pot is a deep well into its own origin story: “an ongoing meditation of where we live in Northern New Mexico,” as Ortiz puts it, “a celebration of its nature and the fleeting of time.”

Wood fired porcelain vase with two different ash glazes, 2020

Porcelain

10 x 7 x 6 1/2 inches

There is something irresistible in Frances Palmer’s practice, which is one level disarmingly straightforward – she makes wood-fired pots, and puts flowers and fruit from her own garden into them – but on another level, wildly ambitious, even visionary. The “still life” arrangements that she creates evoke the lush paintings of the Dutch Golden Age, while her ceramics connect to several currents in international ceramics, among them Chinese celadons and Japanese tea ceremony wares. Palmer synthesizes all of these aesthetic terrains into one lavishly orchestrated whole, optimized for the purposes of the twenty-first century. If you are wary of social media’s effects on the more nuanced aspects of art and design, her Instagram feed may convince you otherwise: it transforms your smartphone screen into a rush of ravishing beauty. But of course, it’s better yet to experience her pots in person, and ideally hold them in your hands, so as to appreciate every fold and crease in their walls, every drip and layer-line in the glazes. Throughout the exhibition, Palmer will be replenishing the vases with flowers from her garden, ensuring that every encounter with her work will be a perfect moment, captured.

Wood fired black stoneware moon vase with tenmoku, kaki and nuka glaze, 2020

Stoneware

8 x 7 x 7 inches

There is something irresistible in Frances Palmer’s practice, which is one level disarmingly straightforward – she makes wood-fired pots, and puts flowers and fruit from her own garden into them – but on another level, wildly ambitious, even visionary. The “still life” arrangements that she creates evoke the lush paintings of the Dutch Golden Age, while her ceramics connect to several currents in international ceramics, among them Chinese celadons and Japanese tea ceremony wares. Palmer synthesizes all of these aesthetic terrains into one lavishly orchestrated whole, optimized for the purposes of the twenty-first century. If you are wary of social media’s effects on the more nuanced aspects of art and design, her Instagram feed may convince you otherwise: it transforms your smartphone screen into a rush of ravishing beauty. But of course, it’s better yet to experience her pots in person, and ideally hold them in your hands, so as to appreciate every fold and crease in their walls, every drip and layer-line in the glazes. Throughout the exhibition, Palmer will be replenishing the vases with flowers from her garden, ensuring that every encounter with her work will be a perfect moment, captured.

Wood fired black stoneware moon vase with ash and oxblood glaze, 2020

Stoneware

9 x 7 x 7 inches

There is something irresistible in Frances Palmer’s practice, which is one level disarmingly straightforward – she makes wood-fired pots, and puts flowers and fruit from her own garden into them – but on another level, wildly ambitious, even visionary. The “still life” arrangements that she creates evoke the lush paintings of the Dutch Golden Age, while her ceramics connect to several currents in international ceramics, among them Chinese celadons and Japanese tea ceremony wares. Palmer synthesizes all of these aesthetic terrains into one lavishly orchestrated whole, optimized for the purposes of the twenty-first century. If you are wary of social media’s effects on the more nuanced aspects of art and design, her Instagram feed may convince you otherwise: it transforms your smartphone screen into a rush of ravishing beauty. But of course, it’s better yet to experience her pots in person, and ideally hold them in your hands, so as to appreciate every fold and crease in their walls, every drip and layer-line in the glazes. Throughout the exhibition, Palmer will be replenishing the vases with flowers from her garden, ensuring that every encounter with her work will be a perfect moment, captured.

Wood fired black stoneware narrow neck vase with oribe and oxblood glazes, 2020

Stoneware

9 x 4 x 4 inches

There is something irresistible in Frances Palmer’s practice, which is one level disarmingly straightforward – she makes wood-fired pots, and puts flowers and fruit from her own garden into them – but on another level, wildly ambitious, even visionary. The “still life” arrangements that she creates evoke the lush paintings of the Dutch Golden Age, while her ceramics connect to several currents in international ceramics, among them Chinese celadons and Japanese tea ceremony wares. Palmer synthesizes all of these aesthetic terrains into one lavishly orchestrated whole, optimized for the purposes of the twenty-first century. If you are wary of social media’s effects on the more nuanced aspects of art and design, her Instagram feed may convince you otherwise: it transforms your smartphone screen into a rush of ravishing beauty. But of course, it’s better yet to experience her pots in person, and ideally hold them in your hands, so as to appreciate every fold and crease in their walls, every drip and layer-line in the glazes. Throughout the exhibition, Palmer will be replenishing the vases with flowers from her garden, ensuring that every encounter with her work will be a perfect moment, captured.

Wood fired black stoneware triangular vase with faceted sides in an ash glaze, 2020

Stoneware

9 x 4 x 4 inches

There is something irresistible in Frances Palmer’s practice, which is one level disarmingly straightforward – she makes wood-fired pots, and puts flowers and fruit from her own garden into them – but on another level, wildly ambitious, even visionary. The “still life” arrangements that she creates evoke the lush paintings of the Dutch Golden Age, while her ceramics connect to several currents in international ceramics, among them Chinese celadons and Japanese tea ceremony wares. Palmer synthesizes all of these aesthetic terrains into one lavishly orchestrated whole, optimized for the purposes of the twenty-first century. If you are wary of social media’s effects on the more nuanced aspects of art and design, her Instagram feed may convince you otherwise: it transforms your smartphone screen into a rush of ravishing beauty. But of course, it’s better yet to experience her pots in person, and ideally hold them in your hands, so as to appreciate every fold and crease in their walls, every drip and layer-line in the glazes. Throughout the exhibition, Palmer will be replenishing the vases with flowers from her garden, ensuring that every encounter with her work will be a perfect moment, captured.

Wood fired black stoneware triangular vase with faceted sides and tenmoku, kaki and nuka glazes, 2020

Stoneware

8 x 3 1/4 x 3 1/4 inches

There is something irresistible in Frances Palmer’s practice, which is one level disarmingly straightforward – she makes wood-fired pots, and puts flowers and fruit from her own garden into them – but on another level, wildly ambitious, even visionary. The “still life” arrangements that she creates evoke the lush paintings of the Dutch Golden Age, while her ceramics connect to several currents in international ceramics, among them Chinese celadons and Japanese tea ceremony wares. Palmer synthesizes all of these aesthetic terrains into one lavishly orchestrated whole, optimized for the purposes of the twenty-first century. If you are wary of social media’s effects on the more nuanced aspects of art and design, her Instagram feed may convince you otherwise: it transforms your smartphone screen into a rush of ravishing beauty. But of course, it’s better yet to experience her pots in person, and ideally hold them in your hands, so as to appreciate every fold and crease in their walls, every drip and layer-line in the glazes. Throughout the exhibition, Palmer will be replenishing the vases with flowers from her garden, ensuring that every encounter with her work will be a perfect moment, captured.

Wood fired black stoneware faceted vase with Shino glaze, 2020

Stoneware

8 1/4 x 3 x 3 inches

There is something irresistible in Frances Palmer’s practice, which is one level disarmingly straightforward – she makes wood-fired pots, and puts flowers and fruit from her own garden into them – but on another level, wildly ambitious, even visionary. The “still life” arrangements that she creates evoke the lush paintings of the Dutch Golden Age, while her ceramics connect to several currents in international ceramics, among them Chinese celadons and Japanese tea ceremony wares. Palmer synthesizes all of these aesthetic terrains into one lavishly orchestrated whole, optimized for the purposes of the twenty-first century. If you are wary of social media’s effects on the more nuanced aspects of art and design, her Instagram feed may convince you otherwise: it transforms your smartphone screen into a rush of ravishing beauty. But of course, it’s better yet to experience her pots in person, and ideally hold them in your hands, so as to appreciate every fold and crease in their walls, every drip and layer-line in the glazes. Throughout the exhibition, Palmer will be replenishing the vases with flowers from her garden, ensuring that every encounter with her work will be a perfect moment, captured.

Wood fired black stoneware faceted vase with straight sides and nuka, kaki and tenmoku glazes, 2020

Stoneware

6 1/2 x 3 1/2 x 3 1/2 inches

There is something irresistible in Frances Palmer’s practice, which is one level disarmingly straightforward – she makes wood-fired pots, and puts flowers and fruit from her own garden into them – but on another level, wildly ambitious, even visionary. The “still life” arrangements that she creates evoke the lush paintings of the Dutch Golden Age, while her ceramics connect to several currents in international ceramics, among them Chinese celadons and Japanese tea ceremony wares. Palmer synthesizes all of these aesthetic terrains into one lavishly orchestrated whole, optimized for the purposes of the twenty-first century. If you are wary of social media’s effects on the more nuanced aspects of art and design, her Instagram feed may convince you otherwise: it transforms your smartphone screen into a rush of ravishing beauty. But of course, it’s better yet to experience her pots in person, and ideally hold them in your hands, so as to appreciate every fold and crease in their walls, every drip and layer-line in the glazes. Throughout the exhibition, Palmer will be replenishing the vases with flowers from her garden, ensuring that every encounter with her work will be a perfect moment, captured.

Wood fired black stoneware oval vase with oribe glaze, 2020

Stoneware

4 1/2 x 3 1/4 x 2 1/2 inches

There is something irresistible in Frances Palmer’s practice, which is one level disarmingly straightforward – she makes wood-fired pots, and puts flowers and fruit from her own garden into them – but on another level, wildly ambitious, even visionary. The “still life” arrangements that she creates evoke the lush paintings of the Dutch Golden Age, while her ceramics connect to several currents in international ceramics, among them Chinese celadons and Japanese tea ceremony wares. Palmer synthesizes all of these aesthetic terrains into one lavishly orchestrated whole, optimized for the purposes of the twenty-first century. If you are wary of social media’s effects on the more nuanced aspects of art and design, her Instagram feed may convince you otherwise: it transforms your smartphone screen into a rush of ravishing beauty. But of course, it’s better yet to experience her pots in person, and ideally hold them in your hands, so as to appreciate every fold and crease in their walls, every drip and layer-line in the glazes. Throughout the exhibition, Palmer will be replenishing the vases with flowers from her garden, ensuring that every encounter with her work will be a perfect moment, captured.

Wood fired porcelain vase with Tenmoku and nuka glaze, 2020

Stoneware

4 1/2 x 3 1/2 inches

There is something irresistible in Frances Palmer’s practice, which is one level disarmingly straightforward – she makes wood-fired pots, and puts flowers and fruit from her own garden into them – but on another level, wildly ambitious, even visionary. The “still life” arrangements that she creates evoke the lush paintings of the Dutch Golden Age, while her ceramics connect to several currents in international ceramics, among them Chinese celadons and Japanese tea ceremony wares. Palmer synthesizes all of these aesthetic terrains into one lavishly orchestrated whole, optimized for the purposes of the twenty-first century. If you are wary of social media’s effects on the more nuanced aspects of art and design, her Instagram feed may convince you otherwise: it transforms your smartphone screen into a rush of ravishing beauty. But of course, it’s better yet to experience her pots in person, and ideally hold them in your hands, so as to appreciate every fold and crease in their walls, every drip and layer-line in the glazes. Throughout the exhibition, Palmer will be replenishing the vases with flowers from her garden, ensuring that every encounter with her work will be a perfect moment, captured.

Wood fired porcelain fluted vase with two ash glazes, 2020

Stoneware

4 1/2 x 3 1/2 x 3 1/2 inches

There is something irresistible in Frances Palmer’s practice, which is one level disarmingly straightforward – she makes wood-fired pots, and puts flowers and fruit from her own garden into them – but on another level, wildly ambitious, even visionary. The “still life” arrangements that she creates evoke the lush paintings of the Dutch Golden Age, while her ceramics connect to several currents in international ceramics, among them Chinese celadons and Japanese tea ceremony wares. Palmer synthesizes all of these aesthetic terrains into one lavishly orchestrated whole, optimized for the purposes of the twenty-first century. If you are wary of social media’s effects on the more nuanced aspects of art and design, her Instagram feed may convince you otherwise: it transforms your smartphone screen into a rush of ravishing beauty. But of course, it’s better yet to experience her pots in person, and ideally hold them in your hands, so as to appreciate every fold and crease in their walls, every drip and layer-line in the glazes. Throughout the exhibition, Palmer will be replenishing the vases with flowers from her garden, ensuring that every encounter with her work will be a perfect moment, captured.

Table Top Vase, 2020

Polyurethane resin, pigment

7 7/8 x 6 inches

Contributed by Salon 94 Design

It’s ridiculous, in a way, to put Gaetano Pesce and potted plants in the same sentence. He is arguably the most influential living designer, a geyser of ideas and provocations that has gushed unabated for over sixty years. Everyone working in speculative, figurative, experimental, conceptual, and process-based modes – which covers almost all of the interesting currents in contemporary design – owes something to him, whether they know it or not. But there’s another thing about Pesce. Nothing is trivial in his eyes, particularly when it comes to our built environment. And so: potted plants. They have been an important part of interior furnishings of the Noyes House since it was built, a way of bringing nature indoors, one of the central principles of the architecture. With this in mind, several of Pesce’s large-scale, poured resin vases have been set around the rooms (in addition to vases in several other scales, and a table-top shelf piece). They transform this modest dimension of the interior into something dramatic, a meeting of two forms of organic life – that of the plants themselves, and that of the intensely artificial objects, which are made of plastic but have the coursing, form-finding energy of vibrantly living things. Over eighty years old now, and given a seemingly supporting role in the installation, Pesce still manages to steal the show.

Tube Vase, 2020

Polyurethane resin, pigment

7 1/2 x 10 inches

Contributed by Salon 94 Design

It’s ridiculous, in a way, to put Gaetano Pesce and potted plants in the same sentence. He is arguably the most influential living designer, a geyser of ideas and provocations that has gushed unabated for over sixty years. Everyone working in speculative, figurative, experimental, conceptual, and process-based modes – which covers almost all of the interesting currents in contemporary design – owes something to him, whether they know it or not. But there’s another thing about Pesce. Nothing is trivial in his eyes, particularly when it comes to our built environment. And so: potted plants. They have been an important part of interior furnishings of the Noyes House since it was built, a way of bringing nature indoors, one of the central principles of the architecture. With this in mind, several of Pesce’s large-scale, poured resin vases have been set around the rooms (in addition to vases in several other scales, and a table-top shelf piece). They transform this modest dimension of the interior into something dramatic, a meeting of two forms of organic life – that of the plants themselves, and that of the intensely artificial objects, which are made of plastic but have the coursing, form-finding energy of vibrantly living things. Over eighty years old now, and given a seemingly supporting role in the installation, Pesce still manages to steal the show.

Drip Vase, 2020

Polyurethane resin, pigment

8 1/2 x 6 inches

Contributed by Salon 94 Design

It’s ridiculous, in a way, to put Gaetano Pesce and potted plants in the same sentence. He is arguably the most influential living designer, a geyser of ideas and provocations that has gushed unabated for over sixty years. Everyone working in speculative, figurative, experimental, conceptual, and process-based modes – which covers almost all of the interesting currents in contemporary design – owes something to him, whether they know it or not. But there’s another thing about Pesce. Nothing is trivial in his eyes, particularly when it comes to our built environment. And so: potted plants. They have been an important part of interior furnishings of the Noyes House since it was built, a way of bringing nature indoors, one of the central principles of the architecture. With this in mind, several of Pesce’s large-scale, poured resin vases have been set around the rooms (in addition to vases in several other scales, and a table-top shelf piece). They transform this modest dimension of the interior into something dramatic, a meeting of two forms of organic life – that of the plants themselves, and that of the intensely artificial objects, which are made of plastic but have the coursing, form-finding energy of vibrantly living things. Over eighty years old now, and given a seemingly supporting role in the installation, Pesce still manages to steal the show.

Drip Vase, 2020

Polyurethane resin, pigment

9 x 10 inches

Contributed by Salon 94 Design

It’s ridiculous, in a way, to put Gaetano Pesce and potted plants in the same sentence. He is arguably the most influential living designer, a geyser of ideas and provocations that has gushed unabated for over sixty years. Everyone working in speculative, figurative, experimental, conceptual, and process-based modes – which covers almost all of the interesting currents in contemporary design – owes something to him, whether they know it or not. But there’s another thing about Pesce. Nothing is trivial in his eyes, particularly when it comes to our built environment. And so: potted plants. They have been an important part of interior furnishings of the Noyes House since it was built, a way of bringing nature indoors, one of the central principles of the architecture. With this in mind, several of Pesce’s large-scale, poured resin vases have been set around the rooms (in addition to vases in several other scales, and a table-top shelf piece). They transform this modest dimension of the interior into something dramatic, a meeting of two forms of organic life – that of the plants themselves, and that of the intensely artificial objects, which are made of plastic but have the coursing, form-finding energy of vibrantly living things. Over eighty years old now, and given a seemingly supporting role in the installation, Pesce still manages to steal the show.

Drip Vase, 2020

Polyurethane resin, pigment

9 x 6 1/4 inches

Contributed by Salon 94 Design

It’s ridiculous, in a way, to put Gaetano Pesce and potted plants in the same sentence. He is arguably the most influential living designer, a geyser of ideas and provocations that has gushed unabated for over sixty years. Everyone working in speculative, figurative, experimental, conceptual, and process-based modes – which covers almost all of the interesting currents in contemporary design – owes something to him, whether they know it or not. But there’s another thing about Pesce. Nothing is trivial in his eyes, particularly when it comes to our built environment. And so: potted plants. They have been an important part of interior furnishings of the Noyes House since it was built, a way of bringing nature indoors, one of the central principles of the architecture. With this in mind, several of Pesce’s large-scale, poured resin vases have been set around the rooms (in addition to vases in several other scales, and a table-top shelf piece). They transform this modest dimension of the interior into something dramatic, a meeting of two forms of organic life – that of the plants themselves, and that of the intensely artificial objects, which are made of plastic but have the coursing, form-finding energy of vibrantly living things. Over eighty years old now, and given a seemingly supporting role in the installation, Pesce still manages to steal the show.

Black Drip Vase, 2019

Polyurethane resin, pigment

27 5/8 x 15 3/4 x 15 3/4 inches

Contributed by Salon 94 Design

It’s ridiculous, in a way, to put Gaetano Pesce and potted plants in the same sentence. He is arguably the most influential living designer, a geyser of ideas and provocations that has gushed unabated for over sixty years. Everyone working in speculative, figurative, experimental, conceptual, and process-based modes – which covers almost all of the interesting currents in contemporary design – owes something to him, whether they know it or not. But there’s another thing about Pesce. Nothing is trivial in his eyes, particularly when it comes to our built environment. And so: potted plants. They have been an important part of interior furnishings of the Noyes House since it was built, a way of bringing nature indoors, one of the central principles of the architecture. With this in mind, several of Pesce’s large-scale, poured resin vases have been set around the rooms (in addition to vases in several other scales, and a table-top shelf piece). They transform this modest dimension of the interior into something dramatic, a meeting of two forms of organic life – that of the plants themselves, and that of the intensely artificial objects, which are made of plastic but have the coursing, form-finding energy of vibrantly living things. Over eighty years old now, and given a seemingly supporting role in the installation, Pesce still manages to steal the show.

Green Drip Vase, 2019

Polyurethane resin, pigment

25 5/8 x 19 3/8 x 19 3/8 inches

Contributed by Salon 94 Design

It’s ridiculous, in a way, to put Gaetano Pesce and potted plants in the same sentence. He is arguably the most influential living designer, a geyser of ideas and provocations that has gushed unabated for over sixty years. Everyone working in speculative, figurative, experimental, conceptual, and process-based modes – which covers almost all of the interesting currents in contemporary design – owes something to him, whether they know it or not. But there’s another thing about Pesce. Nothing is trivial in his eyes, particularly when it comes to our built environment. And so: potted plants. They have been an important part of interior furnishings of the Noyes House since it was built, a way of bringing nature indoors, one of the central principles of the architecture. With this in mind, several of Pesce’s large-scale, poured resin vases have been set around the rooms (in addition to vases in several other scales, and a table-top shelf piece). They transform this modest dimension of the interior into something dramatic, a meeting of two forms of organic life – that of the plants themselves, and that of the intensely artificial objects, which are made of plastic but have the coursing, form-finding energy of vibrantly living things. Over eighty years old now, and given a seemingly supporting role in the installation, Pesce still manages to steal the show.

Large Red Pebble Vase, 2016

Polyurethane resin, pigment

27 5/8 x 10 5/8 inches

Contributed by Salon 94 Design

It’s ridiculous, in a way, to put Gaetano Pesce and potted plants in the same sentence. He is arguably the most influential living designer, a geyser of ideas and provocations that has gushed unabated for over sixty years. Everyone working in speculative, figurative, experimental, conceptual, and process-based modes – which covers almost all of the interesting currents in contemporary design – owes something to him, whether they know it or not. But there’s another thing about Pesce. Nothing is trivial in his eyes, particularly when it comes to our built environment. And so: potted plants. They have been an important part of interior furnishings of the Noyes House since it was built, a way of bringing nature indoors, one of the central principles of the architecture. With this in mind, several of Pesce’s large-scale, poured resin vases have been set around the rooms (in addition to vases in several other scales, and a table-top shelf piece). They transform this modest dimension of the interior into something dramatic, a meeting of two forms of organic life – that of the plants themselves, and that of the intensely artificial objects, which are made of plastic but have the coursing, form-finding energy of vibrantly living things. Over eighty years old now, and given a seemingly supporting role in the installation, Pesce still manages to steal the show.

Self Portrait Shelf, Miniature, 2020

Polyurethane resin, pigment

9 1/2 x 7 1/8 x 2 inches

Contributed by Salon 94 Design

It’s ridiculous, in a way, to put Gaetano Pesce and potted plants in the same sentence. He is arguably the most influential living designer, a geyser of ideas and provocations that has gushed unabated for over sixty years. Everyone working in speculative, figurative, experimental, conceptual, and process-based modes – which covers almost all of the interesting currents in contemporary design – owes something to him, whether they know it or not. But there’s another thing about Pesce. Nothing is trivial in his eyes, particularly when it comes to our built environment. And so: potted plants. They have been an important part of interior furnishings of the Noyes House since it was built, a way of bringing nature indoors, one of the central principles of the architecture. With this in mind, several of Pesce’s large-scale, poured resin vases have been set around the rooms (in addition to vases in several other scales, and a table-top shelf piece). They transform this modest dimension of the interior into something dramatic, a meeting of two forms of organic life – that of the plants themselves, and that of the intensely artificial objects, which are made of plastic but have the coursing, form-finding energy of vibrantly living things. Over eighty years old now, and given a seemingly supporting role in the installation, Pesce still manages to steal the show.

Photo by Meredith Heuer

Relative, 2020

Glazed ceramic, wood, paint and steel

23 x 13 x 30 inches

Contributed by Pace Gallery

Art historical trajectories never really end. They just keep going, accumulating innovations and associations all along the way. But if for some reason you had to draw a line forward from the great modern sculptors – Brancusi, Hepworth Calder and the rest – and stop somewhere, the work of Arlene Shechet would be a great choice. Ecumenical in her materials (best known for her pioneering reintroduction of ceramic into contemporary art, she also works in wood, metal and other media) and incredibly inventive in her forms, which often develop contrapuntally as one walks around them, she gives you everything you ever wanted from sculpture, as well as quite a few things you didn’t even know you could have. For At the Noyes House, she is showing a new work called Relative, fairly compact and low to the ground. Made especially for the exhibition, it speaks harmoniously to the setting, with rigid squares intersecting an unfinished wood block – like a core section of the rectilinear building’s encounter with the surrounding forest.

Courtesy of Friedman Benda

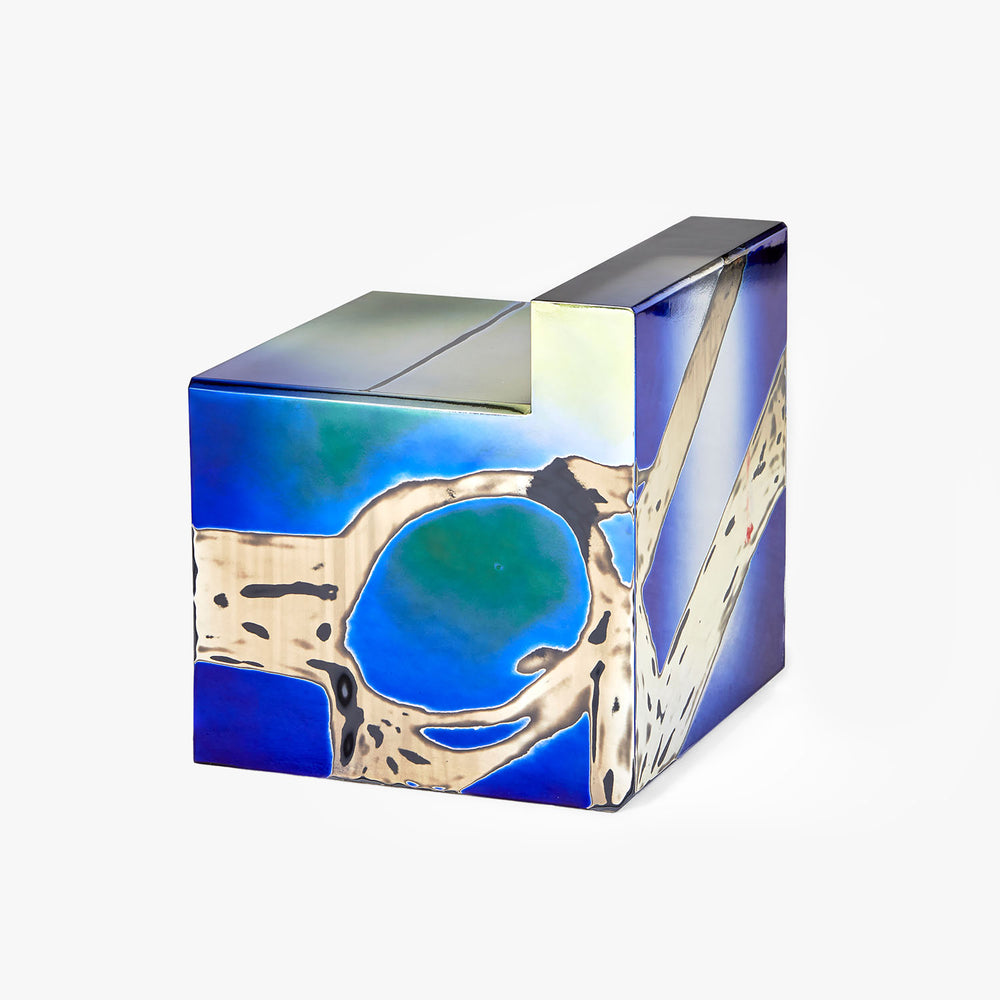

Maquette 061 / Clay Seat Tapestry, 2020

Wool, cotton

28 1/4 x 42 1/4 inches

Contributed by Friedman Benda