The Gallery at Stone Barns

In Collaboration with Object & Thing

March 31 – May 9, 2021

Pocantico Hills, NY

Photo by Elena Wolfe

Use left/right arrows to navigate the slideshow or swipe left/right if using a mobile device

Object & Thing joined Stone Barns Center in collaborating on the first exhibition in a new Gallery space at the nonprofit farm and education center in Pocantico Hills, New York. This exhibition celebrated the linkages between artistic practices and farm sustainability. Object & Thing’s curation of the exhibition focused on artists it champions that share a deep awareness and reverence for the origin of the materials that inform their practices. The participating artists were: Megumi Arai, Jane Crisp, Green River Project LLC, Gregg Moore, Kiva Motnyk, Johnny Ortiz and Frances Palmer. Artists were offered the opportunity to visit with the Arts & Ecology team at Stone Barns Center in order to identify materials for their pieces. The overall display involved surfaces designed by Object & Thing’s artistic director, Rafael de Cárdenas, which were debuted at the inaugural edition of Object & Thing in Brooklyn. Artist Frances Palmer joined Philippe Gouze, Stone Barns Center’s co-director of Arts & Ecology, in creating floral installations in response to the change of season throughout the exhibition. All of the works in the exhibition were available for sale, with a percentage of proceeds benefiting Stone Barns Center. A related educational program involving talks and workshops with the participating artists was also offered by Stone Barns Center.

Installation Views

Photo by Elena Wolfe

Photo by Elena Wolfe

Photo by Elena Wolfe

Photo by Elena Wolfe

Photo by Elena Wolfe

Photo by Elena Wolfe

Photo by Elena Wolfe

Photo by Elena Wolfe

Photo by Elena Wolfe

Rite of Spring

Paris, 29 May 1913, evening. The trees have come into leaf across the city. Flowers fill the parks. And at the newly built Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, people are screaming bloody murder. It is the premiere of Igor Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps, a composition and choreography so modern that the audience, whether in rage or excitement or some combination of the two, quite loses its collective mind.

Spring doesn’t usually arrive with such evident force. It seems the kindliest of seasons — the arrival of new life, and all that. Yet the notorious furor set off by Stravinsky’s dissonant masterpiece directs our attention to what’s really going on, out there beyond our walls: the sheer explosive power of spring, all those seeds and bulbs bursting the ground asunder, sap running free, plants stretching themselves upwards to receive the light. Most people simply watch it all unfolding, like an audience set comfortably back from a stage. Gardeners are more in tune, channeling natural potency into neatly circumscribed beds. But comparatively few of us, these days, put themselves fully in the way of the seasons, allowing their cyclical energies to shape their own daily round.

That’s what’s happening, day in, day out, at Stone Barns Center. Developed on the site of an old dairy farm, the organization has itself grown organically since its opening in 2004, connecting farmers to cooks in pursuit of an ecological food culture alongside its partner Blue Hill at Stone Barns. The phrase “farm to table” only hints at the interlinked systems of the place, though: dining room, kitchen, farm, greenhouse, pastures, slaughterhouse, educational programs, and — now — a gallery, all combining in glorious harmony.

The present collaboration with the itinerant art and design fair, Object & Thing, is the latest outgrowth of this holistic method. Every aspect of the seven-artist presentation involves materials or display elements sourced from the Stone Barns property: clay dug from the earth, dye materials harvested from plants, stones retrieved from the ground, fresh-cut branches and blossoms placed in baskets and pots. In so many ways, the exemplary works on view are sympathetic with everything else that grows here: the unique outgrowth of a unique moment in time.

Will the public, seeing this beautifully formed exhibition, be as moved to passionate response as those Parisians were a century ago? Maybe so. Not to outrage, of course. But perhaps some other emotion, equally profound, propelled by the forces released all around. The feeling of spring, sprung.

By Glenn Adamson

Artists

Megumi Arai

Jane Crisp

Green River Project LLC

Gregg Moore

Kiva Motnyk

Johnny Ortiz

Frances Palmer

Works in the Exhibition

Courtesy of the artist and Tiwa Select, photo by Chris Mottalini

Noren (large), 2021

Silk, linens and loose-weave cottons dyed with sumac, marigold, onion skin, dahlia and iron, and found fabrics from Japan, Eastern Europe and France; hazel branch; hazel branch from the farm

43 x 48 inches

Japanese noren hangings are used to mark transitions: liminal states, not just of place, but also of time. What more appropriate greeting could visitors have to the gallery at Stone Barns — a new space, opened at a new season. And not just any season, but one that marks many people’s emergence from a long, unusually sequestered winter. This welcome is offered by Megumi Arai (b. 1989, Portland, OR, USA), who specializes in boro textiles, whose dynamic abstract patterns are composed of many re-used fabric scraps. Though spectacular in their palette, their beauty is patient and hard-won, paying implicit tribute to the historical originators and custodians of the tradition. For her Stone Barns noren, Arai incorporates found fabrics, as well as fabric with natural dyes developed from plants from the farm — another kind of salvage, another way of honoring.

Courtesy of the artist and Tiwa Select

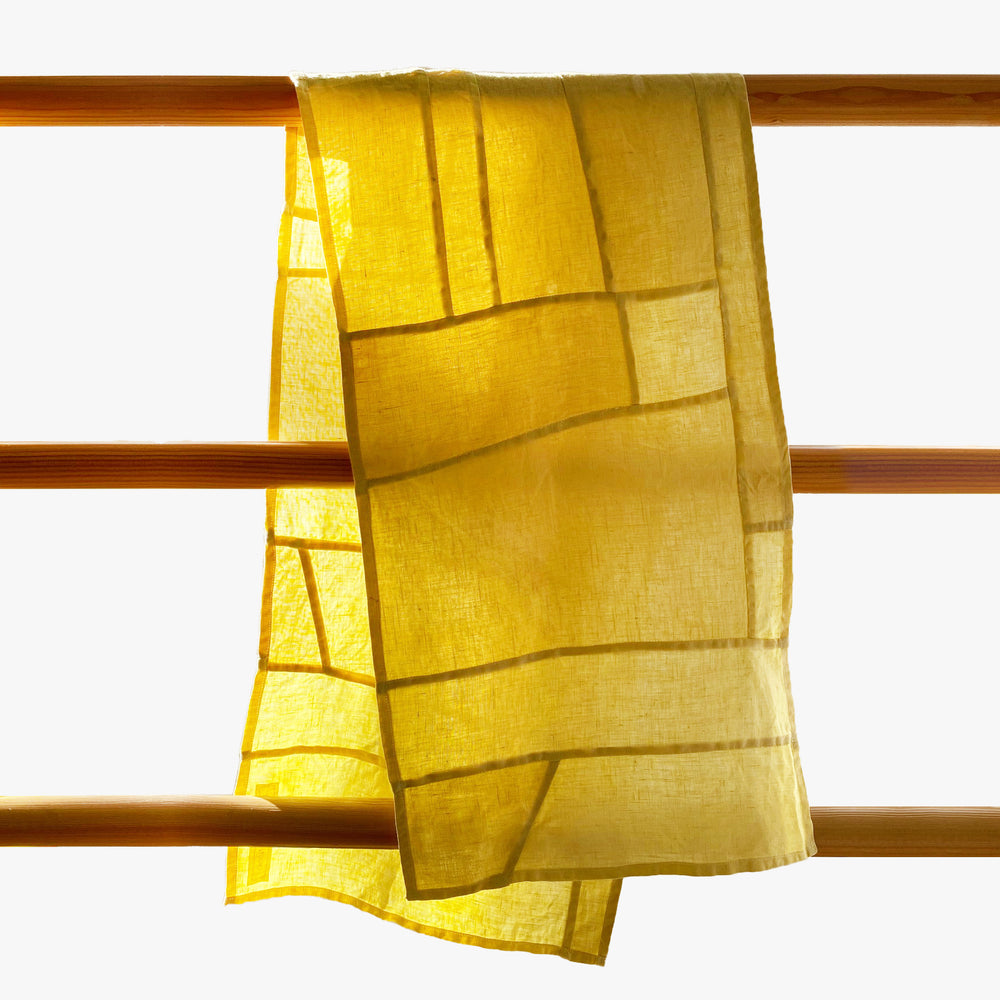

Noren (medium), 2021

Silk, linens and loose-weave cottons dyed with Stone Barns grown sumac, marigold, onion skin, dahlia and iron, and found fabrics from Japan, Eastern Europe and France; hazel branch from the farm

38 x 48 inches

Japanese noren hangings are used to mark transitions: liminal states, not just of place, but also of time. What more appropriate greeting could visitors have to the gallery at Stone Barns — a new space, opened at a new season. And not just any season, but one that marks many people’s emergence from a long, unusually sequestered winter. This welcome is offered by Megumi Arai (b. 1989, Portland, OR, USA), who specializes in boro textiles, whose dynamic abstract patterns are composed of many re-used fabric scraps. Though spectacular in their palette, their beauty is patient and hard-won, paying implicit tribute to the historical originators and custodians of the tradition. For her Stone Barns noren, Arai incorporates found fabrics, as well as fabric with natural dyes developed from plants from the farm — another kind of salvage, another way of honoring.

Courtesy of the artist and Tiwa Select

Noren (small), 2021

Silk, linens and loose-weave cottons dyed with Stone Barns grown sumac, marigold, onion skin, dahlia and iron, and found fabrics from Japan, Eastern Europe and France; hazel branch from the farm

32 x 36 inches

Japanese noren hangings are used to mark transitions: liminal states, not just of place, but also of time. What more appropriate greeting could visitors have to the gallery at Stone Barns — a new space, opened at a new season. And not just any season, but one that marks many people’s emergence from a long, unusually sequestered winter. This welcome is offered by Megumi Arai (b. 1989, Portland, OR, USA), who specializes in boro textiles, whose dynamic abstract patterns are composed of many re-used fabric scraps. Though spectacular in their palette, their beauty is patient and hard-won, paying implicit tribute to the historical originators and custodians of the tradition. For her Stone Barns noren, Arai incorporates found fabrics, as well as fabric with natural dyes developed from plants from the farm — another kind of salvage, another way of honoring.

Courtesy of the artist and Tiwa Select

Noren (small), 2021

Silk, linens and loose-weave cottons dyed with Stone Barns grown sumac, marigold, onion skin, dahlia and iron, and found fabrics from Japan, Eastern Europe and France; hazel branch from the farm

32 x 36 inches

Japanese noren hangings are used to mark transitions: liminal states, not just of place, but also of time. What more appropriate greeting could visitors have to the gallery at Stone Barns — a new space, opened at a new season. And not just any season, but one that marks many people’s emergence from a long, unusually sequestered winter. This welcome is offered by Megumi Arai (b. 1989, Portland, OR, USA), who specializes in boro textiles, whose dynamic abstract patterns are composed of many re-used fabric scraps. Though spectacular in their palette, their beauty is patient and hard-won, paying implicit tribute to the historical originators and custodians of the tradition. For her Stone Barns noren, Arai incorporates found fabrics, as well as fabric with natural dyes developed from plants from the farm — another kind of salvage, another way of honoring.

Courtesy of the artist and Tiwa Select

Noren (small), 2021

Silk, linens and loose-weave cottons dyed with Stone Barns grown sumac, marigold, onion skin, dahlia and iron, and found fabrics from Japan, Eastern Europe and France; hazel branch from the farm

38 x 48 inches

Japanese noren hangings are used to mark transitions: liminal states, not just of place, but also of time. What more appropriate greeting could visitors have to the gallery at Stone Barns — a new space, opened at a new season. And not just any season, but one that marks many people’s emergence from a long, unusually sequestered winter. This welcome is offered by Megumi Arai (b. 1989, Portland, OR, USA), who specializes in boro textiles, whose dynamic abstract patterns are composed of many re-used fabric scraps. Though spectacular in their palette, their beauty is patient and hard-won, paying implicit tribute to the historical originators and custodians of the tradition. For her Stone Barns noren, Arai incorporates found fabrics, as well as fabric with natural dyes developed from plants from the farm — another kind of salvage, another way of honoring.

Courtesy of the artist and Tiwa Select

Noren (small), 2021

Silk, linens and loose-weave cottons dyed with Stone Barns grown sumac, marigold, onion skin, dahlia and iron, and found fabrics from Japan, Eastern Europe and France; hazel branch from the farm

32 x 36 inches

Japanese noren hangings are used to mark transitions: liminal states, not just of place, but also of time. What more appropriate greeting could visitors have to the gallery at Stone Barns — a new space, opened at a new season. And not just any season, but one that marks many people’s emergence from a long, unusually sequestered winter. This welcome is offered by Megumi Arai (b. 1989, Portland, OR, USA), who specializes in boro textiles, whose dynamic abstract patterns are composed of many re-used fabric scraps. Though spectacular in their palette, their beauty is patient and hard-won, paying implicit tribute to the historical originators and custodians of the tradition. For her Stone Barns noren, Arai incorporates found fabrics, as well as fabric with natural dyes developed from plants from the farm — another kind of salvage, another way of honoring.

Natasha Biggs, YOUR Photography & Creative Marketing

Ash Log Trug, 2021

Steam-bent ash, copper nails and roves finished with natural hard wax oil

16 x 22 x 17 inches

A trug, traditionally, is a shallow basket made from wooden strips, intended for light duty — marketing or gardening, perhaps. While this narrow description does fit Jane Crisp’s (b. 1980, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, UK) reinvention of the form, it leaves a lot unsaid. To the conventional repertoire, she has added skills drawn from her own experience as a furniture maker who has also been inspired by boat-building practices and materials: steam-bending, copper nails, and an overlapping “clinker” construction. These techniques allow her to create shapes that are indeed somewhat redolent of a ship’s hull, or perhaps a bird’s wing, folding in upon itself. Crisp, who has also lived on a narrow boat, cites riverbank reeds as an inspiration for her forms. But the real value in these elegant objects is not so much in their references, the technical aspects of their construction, or even the personal experiences that they reflect. No: it is the way they sit within space and time, poised and confident. In their vertiginous spiraling lines, we see the trajectories of past and present intersecting.

Natasha Biggs, YOUR Photography & Creative Marketing

Cherry Forager, 2021

Steam-bent cherry, copper nails and roves finished with natural hard wax oil

15 x 18 x 14.25 inches

A trug, traditionally, is a shallow basket made from wooden strips, intended for light duty — marketing or gardening, perhaps. While this narrow description does fit Jane Crisp’s (b. 1980, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, UK) reinvention of the form, it leaves a lot unsaid. To the conventional repertoire, she has added skills drawn from her own experience as a furniture maker who has also been inspired by boat-building practices and materials: steam-bending, copper nails, and an overlapping “clinker” construction. These techniques allow her to create shapes that are indeed somewhat redolent of a ship’s hull, or perhaps a bird’s wing, folding in upon itself. Crisp, who has also lived on a narrow boat, cites riverbank reeds as an inspiration for her forms. But the real value in these elegant objects is not so much in their references, the technical aspects of their construction, or even the personal experiences that they reflect. No: it is the way they sit within space and time, poised and confident. In their vertiginous spiraling lines, we see the trajectories of past and present intersecting.

Natasha Biggs, YOUR Photography & Creative Marketing

Olive Ash Forager, 2021

Steam-bent olive ash, copper nails and roves finished with natural hard wax oil

15 x 17 x 14.5 inches

A trug, traditionally, is a shallow basket made from wooden strips, intended for light duty — marketing or gardening, perhaps. While this narrow description does fit Jane Crisp’s (b. 1980, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, UK) reinvention of the form, it leaves a lot unsaid. To the conventional repertoire, she has added skills drawn from her own experience as a furniture maker who has also been inspired by boat-building practices and materials: steam-bending, copper nails, and an overlapping “clinker” construction. These techniques allow her to create shapes that are indeed somewhat redolent of a ship’s hull, or perhaps a bird’s wing, folding in upon itself. Crisp, who has also lived on a narrow boat, cites riverbank reeds as an inspiration for her forms. But the real value in these elegant objects is not so much in their references, the technical aspects of their construction, or even the personal experiences that they reflect. No: it is the way they sit within space and time, poised and confident. In their vertiginous spiraling lines, we see the trajectories of past and present intersecting.

Wood Vessel, 2021

Vessel carved from black cherry wood from Stone Barns

10 x 10 x 6 inches

Founded in 2017 by Aaron Aujla (b. 1986, Victoria, Canada) and Benjamin Bloomstein (b. 1988, Hillsdale, NY, USA), Green River Project LLC is a research-driven New York City workshop, both in its use of materials and in its relationship to design history. Each Green River creation is unique, while expressing a single common set of principles. Forthrightness is Aujla and Bloomstein’s prime directive; they employ straightforward, often massive joinery and carving techniques. The apparent simplicity is, to some extent, deceiving; their forms draw in a sophisticated way on precedents in the canon of modernism, like Gerrit Rietveld, Alexandre Noll, and Constantin Brancusi. Yet their work is also completely right for today — today, when just about everything is inflected by spin, experienced through some filter or other, at a distance from the actual. Green River remedies this through the simple fact of encounter (in the present exhibition, using wood found on the Stone Barns property). Every one of their works is an anchor for experience, solid and assured. And goodness knows, we could all use more of that.

Wood Vessel, 2021

Vessel carved from black cherry wood from Stone Barns

10 x 10 x 6 inches

Founded in 2017 by Aaron Aujla (b. 1986, Victoria, Canada) and Benjamin Bloomstein (b. 1988, Hillsdale, NY, USA), Green River Project LLC is a research-driven New York City workshop, both in its use of materials and in its relationship to design history. Each Green River creation is unique, while expressing a single common set of principles. Forthrightness is Aujla and Bloomstein’s prime directive; they employ straightforward, often massive joinery and carving techniques. The apparent simplicity is, to some extent, deceiving; their forms draw in a sophisticated way on precedents in the canon of modernism, like Gerrit Rietveld, Alexandre Noll, and Constantin Brancusi. Yet their work is also completely right for today — today, when just about everything is inflected by spin, experienced through some filter or other, at a distance from the actual. Green River remedies this through the simple fact of encounter (in the present exhibition, using wood found on the Stone Barns property). Every one of their works is an anchor for experience, solid and assured. And goodness knows, we could all use more of that.

Wood Vessel, 2021

Vessel carved from black cherry wood from Stone Barns

14 x 10 x 6 inches

Founded in 2017 by Aaron Aujla (b. 1986, Victoria, Canada) and Benjamin Bloomstein (b. 1988, Hillsdale, NY, USA), Green River Project LLC is a research-driven New York City workshop, both in its use of materials and in its relationship to design history. Each Green River creation is unique, while expressing a single common set of principles. Forthrightness is Aujla and Bloomstein’s prime directive; they employ straightforward, often massive joinery and carving techniques. The apparent simplicity is, to some extent, deceiving; their forms draw in a sophisticated way on precedents in the canon of modernism, like Gerrit Rietveld, Alexandre Noll, and Constantin Brancusi. Yet their work is also completely right for today — today, when just about everything is inflected by spin, experienced through some filter or other, at a distance from the actual. Green River remedies this through the simple fact of encounter (in the present exhibition, using wood found on the Stone Barns property). Every one of their works is an anchor for experience, solid and assured. And goodness knows, we could all use more of that.

Wood Vessel, 2021

Vessel carved from black cherry wood from Stone Barns

14 x 10 x 6 inches

Founded in 2017 by Aaron Aujla (b. 1986, Victoria, Canada) and Benjamin Bloomstein (b. 1988, Hillsdale, NY, USA), Green River Project LLC is a research-driven New York City workshop, both in its use of materials and in its relationship to design history. Each Green River creation is unique, while expressing a single common set of principles. Forthrightness is Aujla and Bloomstein’s prime directive; they employ straightforward, often massive joinery and carving techniques. The apparent simplicity is, to some extent, deceiving; their forms draw in a sophisticated way on precedents in the canon of modernism, like Gerrit Rietveld, Alexandre Noll, and Constantin Brancusi. Yet their work is also completely right for today — today, when just about everything is inflected by spin, experienced through some filter or other, at a distance from the actual. Green River remedies this through the simple fact of encounter (in the present exhibition, using wood found on the Stone Barns property). Every one of their works is an anchor for experience, solid and assured. And goodness knows, we could all use more of that.

Wood Vessel, 2021

Vessel carved from black cherry wood from Stone Barns

16 x 12 x 9 inches

Founded in 2017 by Aaron Aujla (b. 1986, Victoria, Canada) and Benjamin Bloomstein (b. 1988, Hillsdale, NY, USA), Green River Project LLC is a research-driven New York City workshop, both in its use of materials and in its relationship to design history. Each Green River creation is unique, while expressing a single common set of principles. Forthrightness is Aujla and Bloomstein’s prime directive; they employ straightforward, often massive joinery and carving techniques. The apparent simplicity is, to some extent, deceiving; their forms draw in a sophisticated way on precedents in the canon of modernism, like Gerrit Rietveld, Alexandre Noll, and Constantin Brancusi. Yet their work is also completely right for today — today, when just about everything is inflected by spin, experienced through some filter or other, at a distance from the actual. Green River remedies this through the simple fact of encounter (in the present exhibition, using wood found on the Stone Barns property). Every one of their works is an anchor for experience, solid and assured. And goodness knows, we could all use more of that.

Soil Plate, 2021

50% fired soil dug from below the vegetable field at Stone Barns, 50% porcelain

Size varies among each unique plate with range between 10-13 in diameter; image is not representative of the exact work

For six of the seven artists in the current exhibition, Stone Barns is a site of new exploration. But not Gregg Moore (b. 1975, Hackensack, NJ, USA). He has been collaborating with Chef Dan Barber and the rest of the team at Blue Hill for several years, integrating his practice as a potter with the rhythms and philosophy of the place. Their collaborative experiments have ranged widely: china made of calcined bones from the kitchen, plates textured by pecking hens and rooting pigs, platters cast in farmland furrows. The most essential (a foundation, as it were, for the other, more elaborately conceived pieces) is a series of “soil plates.” They are composed of half Stone Barns dirt, dug up by Stone Barns’ head farmer, Jack Algiere, from the most clay-rich level of the fields’ stratigraphy. The other half is Moore’s own black porcelain recipe, which was itself developed in response to a plate that Barber had given him early in their collaboration. Given this composition, Moore considers the pieces to be "half farmer, half chef…an invitation for discussion of the role of humans with food and ecology."

Photo by Thompson Street Studio

Marigold Dyed Runner and Napkins (set of 4), 2021

Hand dyed patchwork runner with a set of 4 napkins dyed in natural marigold grown at Stone Barns, 100% linen remnants

Runner: 14 in x 56 in; Napkins: 20 in x 20 in; each piece is hand-dyed and colors may vary

“The trees are coming into leaf,” wrote poet Philip Larkin, “like something almost being said.” It’s a wonderful line, which captures the articulateness of nature — its potential to communicate with us — but also the way that it stands apart from us. Nature nurtures a language that is not quite our own. Art at its best can be a kind of translator, bridging that space of the “almost said.” Case in point: the work of Kiva Motnyk (b. 1977, New York, NY, USA). Since 2014, she has been the head of Thompson Street Studio, drawing on a background in high fashion to create textiles infused with natural dyes derived from foraged plants. The linen designs she shows here at Stone Barns feature the colors of the surrounding countryside. Each is a little metaphorical map, a piece of the landscape made eloquent. To quote Larkin again: “Last year is dead, they seem to say / Begin afresh, afresh, afresh.”

Photo by Thompson Street Studio

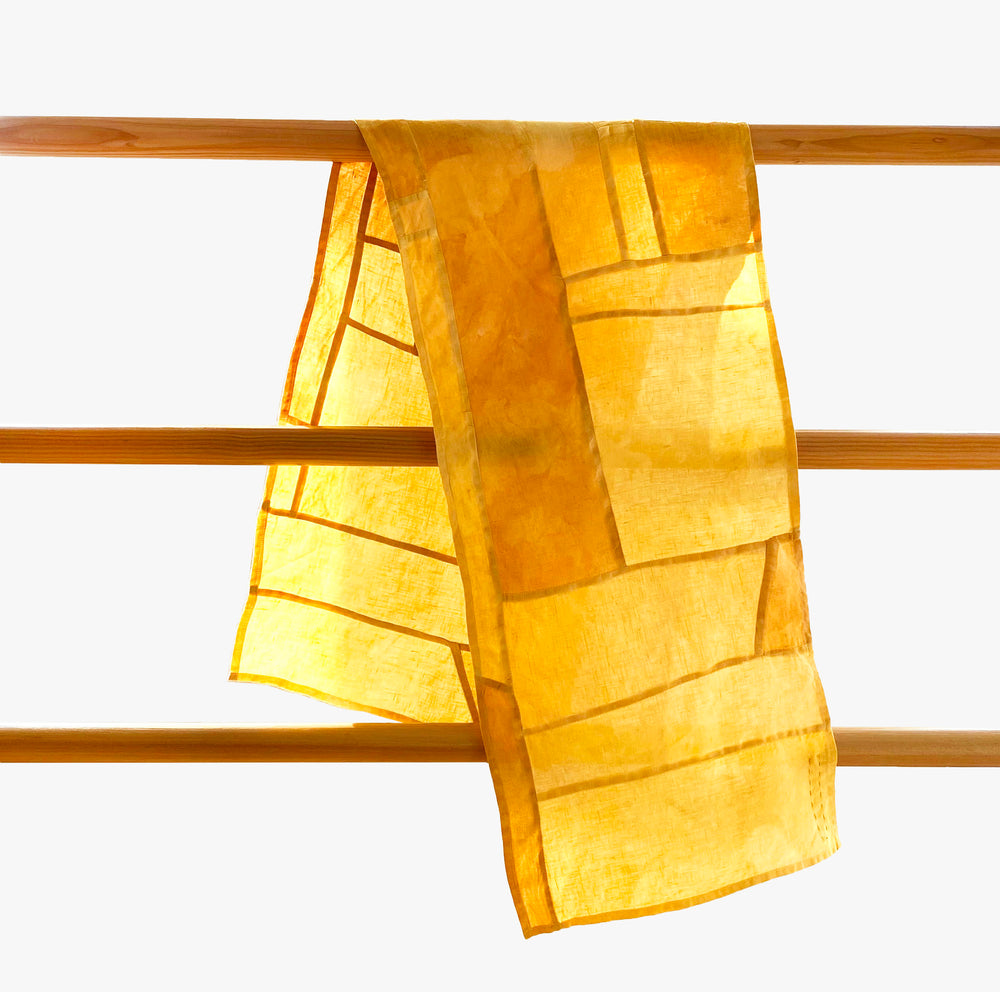

Onion Dyed Runner and Napkins (set of 2), 2021

Hand dyed patchwork runner with a set of 2 napkins dyed with onion from the Blue Hill at Stone Barns kitchen, 100% linen remnants

Runner: 14 in x 56 in; Napkins: 20 in x 20 in; each piece is hand-dyed and colors may vary

“The trees are coming into leaf,” wrote poet Philip Larkin, “like something almost being said.” It’s a wonderful line, which captures the articulateness of nature — its potential to communicate with us — but also the way that it stands apart from us. Nature nurtures a language that is not quite our own. Art at its best can be a kind of translator, bridging that space of the “almost said.” Case in point: the work of Kiva Motnyk (b. 1977, New York, NY, USA). Since 2014, she has been the head of Thompson Street Studio, drawing on a background in high fashion to create textiles infused with natural dyes derived from foraged plants. The linen designs she shows here at Stone Barns feature the colors of the surrounding countryside. Each is a little metaphorical map, a piece of the landscape made eloquent. To quote Larkin again: “Last year is dead, they seem to say / Begin afresh, afresh, afresh.”

Photo by Thompson Street Studio

Mixed Flower Dyed Runner and Napkins (set of 4), 2021

Hand dyed patchwork runner with a set of 4 napkins dyed with mixed flowers grown at Stone Barns, 100% linen remnants

Runner: 14 in x 56 in; Napkins: 20 in x 20 in; each piece is hand-dyed and colors may vary

“The trees are coming into leaf,” wrote poet Philip Larkin, “like something almost being said.” It’s a wonderful line, which captures the articulateness of nature — its potential to communicate with us — but also the way that it stands apart from us. Nature nurtures a language that is not quite our own. Art at its best can be a kind of translator, bridging that space of the “almost said.” Case in point: the work of Kiva Motnyk (b. 1977, New York, NY, USA). Since 2014, she has been the head of Thompson Street Studio, drawing on a background in high fashion to create textiles infused with natural dyes derived from foraged plants. The linen designs she shows here at Stone Barns feature the colors of the surrounding countryside. Each is a little metaphorical map, a piece of the landscape made eloquent. To quote Larkin again: “Last year is dead, they seem to say / Begin afresh, afresh, afresh.”

Photo by Thompson Street Studio

Indigo Dyed Runner and Napkins (set of 4), 2021

Hand dyed patchwork runner with a set of 4 napkins dyed with indigo grown at Stone Barns, 100% linen remnants

Runner: 14 in x 56 in; Napkins: 20 in x 20 in; each piece is hand-dyed and colors may vary

“The trees are coming into leaf,” wrote poet Philip Larkin, “like something almost being said.” It’s a wonderful line, which captures the articulateness of nature — its potential to communicate with us — but also the way that it stands apart from us. Nature nurtures a language that is not quite our own. Art at its best can be a kind of translator, bridging that space of the “almost said.” Case in point: the work of Kiva Motnyk (b. 1977, New York, NY, USA). Since 2014, she has been the head of Thompson Street Studio, drawing on a background in high fashion to create textiles infused with natural dyes derived from foraged plants. The linen designs she shows here at Stone Barns feature the colors of the surrounding countryside. Each is a little metaphorical map, a piece of the landscape made eloquent. To quote Larkin again: “Last year is dead, they seem to say / Begin afresh, afresh, afresh.”

Photo by Johnny Ortiz

Field Studies, 2021

Clay remnant from New Mexico, cured with Stone Barns’ beef tallow and beeswax

Available as a group of three or one large; Size varies among each unique piece; image is not representative of the exact work

Johnny Ortiz (b. 1991, Taos, NM, USA) digs deep in his work — literally. His primary ceramic material is micaceous “wild clay,” found in his home state of New Mexico. When he first discovered this resource, his first instinct was to leave it in the ground: it seemed, he says, “too stunning to do anything with.” But he gradually came to grips with it, seeing in the clay a means of connecting to his own ancestral past, as well as to present-day aesthetic possibilities. He makes the material his own through an elaborate series of procedures, first burnishing the pots with rough sandstone and then smoother river stone, pit firing them with red mountain cedar, and finally, “curing” them with elk marrow and beeswax. For this presentation at Stone Barns Center (concurrent with his time as Chef in Residence at Stone Barns), he is extending his series of “field studies” working with clay from New Mexico, fired at Stone Barns during the late March Worm Moon.

Photo by Maida Branch and Johnny Ortiz

Ceramic Vessel, 2021

Micaceous earth from Northern New Mexico, sanded with local sandstone, burnished with a river stone, pit fired with red cedar and cured with elk marrow and beeswax

3 x 4 x 4 Inches

Johnny Ortiz (b. 1991, Taos, NM, USA) digs deep in his work — literally. His primary ceramic material is micaceous “wild clay,” found in his home state of New Mexico. When he first discovered this resource, his first instinct was to leave it in the ground: it seemed, he says, “too stunning to do anything with.” But he gradually came to grips with it, seeing in the clay a means of connecting to his own ancestral past, as well as to present-day aesthetic possibilities. He makes the material his own through an elaborate series of procedures, first burnishing the pots with rough sandstone and then smoother river stone, pit firing them with red mountain cedar, and finally, “curing” them with elk marrow and beeswax. For this presentation at Stone Barns Center (concurrent with his time as Chef in Residence at Stone Barns), he is extending his series of “field studies” working with clay from New Mexico, fired at Stone Barns during the late March Worm Moon.

Photo by Maida Branch and Johnny Ortiz

Ceramic Vessel, 2021

Micaceous earth from Northern New Mexico, sanded with local sandstone, burnished with a river stone, pit fired with red cedar and cured with elk marrow and beeswax

4.5 x 4 x 4 Inches

Johnny Ortiz (b. 1991, Taos, NM, USA) digs deep in his work — literally. His primary ceramic material is micaceous “wild clay,” found in his home state of New Mexico. When he first discovered this resource, his first instinct was to leave it in the ground: it seemed, he says, “too stunning to do anything with.” But he gradually came to grips with it, seeing in the clay a means of connecting to his own ancestral past, as well as to present-day aesthetic possibilities. He makes the material his own through an elaborate series of procedures, first burnishing the pots with rough sandstone and then smoother river stone, pit firing them with red mountain cedar, and finally, “curing” them with elk marrow and beeswax. For this presentation at Stone Barns Center (concurrent with his time as Chef in Residence at Stone Barns), he is extending his series of “field studies” working with clay from New Mexico, fired at Stone Barns during the late March Worm Moon.

Photo by Maida Branch and Johnny Ortiz

Ceramic Vessel, 2021

Micaceous earth from Northern New Mexico, sanded with local sandstone, burnished with a river stone, pit fired with red cedar and cured with elk marrow and beeswax

3.25 x 4.5 x 4.5 Inches

Johnny Ortiz (b. 1991, Taos, NM, USA) digs deep in his work — literally. His primary ceramic material is micaceous “wild clay,” found in his home state of New Mexico. When he first discovered this resource, his first instinct was to leave it in the ground: it seemed, he says, “too stunning to do anything with.” But he gradually came to grips with it, seeing in the clay a means of connecting to his own ancestral past, as well as to present-day aesthetic possibilities. He makes the material his own through an elaborate series of procedures, first burnishing the pots with rough sandstone and then smoother river stone, pit firing them with red mountain cedar, and finally, “curing” them with elk marrow and beeswax. For this presentation at Stone Barns Center (concurrent with his time as Chef in Residence at Stone Barns), he is extending his series of “field studies” working with clay from New Mexico, fired at Stone Barns during the late March Worm Moon.

Photo by Maida Branch and Johnny Ortiz

Ceramic Vessel, 2021

Micaceous earth from Northern New Mexico, sanded with local sandstone, burnished with a river stone, pit fired with red cedar and cured with elk marrow and beeswax

3.5 x 6.5 x 6.5 Inches

Johnny Ortiz (b. 1991, Taos, NM, USA) digs deep in his work — literally. His primary ceramic material is micaceous “wild clay,” found in his home state of New Mexico. When he first discovered this resource, his first instinct was to leave it in the ground: it seemed, he says, “too stunning to do anything with.” But he gradually came to grips with it, seeing in the clay a means of connecting to his own ancestral past, as well as to present-day aesthetic possibilities. He makes the material his own through an elaborate series of procedures, first burnishing the pots with rough sandstone and then smoother river stone, pit firing them with red mountain cedar, and finally, “curing” them with elk marrow and beeswax. For this presentation at Stone Barns Center (concurrent with his time as Chef in Residence at Stone Barns), he is extending his series of “field studies” working with clay from New Mexico, fired at Stone Barns during the late March Worm Moon.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Eye Hieroglyph Cup, 2021

Wood fired black stoneware eye hieroglyph cup with tenmoku and nuka glaze inside

4 x 6.5 x 4.25 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Eye Hieroglyph Cup, 2021

Wood fired black stoneware eye hieroglyph cup with tea dust glaze inside

4.5 x 6 x 5 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Eye Hieroglyph Cup, 2021

Wood fired stoneware eye hieroglyph cup with tea dust glaze inside and out

4 x 6 x 4 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Eye Hieroglyph Cup, 2021

Wood fired stoneware eye hieroglyph cup with tenmoku and nuka glaze inside and flashing slip outside

4 x 6.5 x 3 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Eye Hieroglyph Cup, 2021

Wood fired stoneware eye hieroglyph cup with tea dust glaze inside and flashing slip outside

4.5 x 5.5 x 3.5 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Pitcher, 2021

Wood fired black stoneware pitcher with tenmoku and nuka glaze inside and out

5.5 x 6 x 3.25 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Pitcher, 2021

Wood fired black stoneware pitcher with tea dust glaze inside and out

6 x 6 x 3 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Pitcher, 2021

Wood fired stoneware pitcher with tea dust glaze inside and out

6.5 x 7 x 4 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Pitcher, 2021

Wood fired black stoneware pitcher with tenmoku and nuka glaze inside and out

6.5 x 7 x 4.5 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Pitcher, 2021

Wood fired black marbleized stoneware pitcher with celadon glaze

6.5 x 6.5 x 3.5 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Pitcher, 2021

Wood fired black marbleized stoneware pitcher with ash glaze inside and out

7.5 x 6.5 x 5 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Pitcher, 2021

Wood fired black marbleized stoneware pitcher with ash glaze inside and out

7 x 6.5 x 4.5 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Pitcher, 2021

Wood fired marbleized stoneware pitcher with tenmoku and nuka glaze inside and out

7.5 x 6.5 x 4.5 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Pitcher, 2021

Wood fired black stoneware pitcher with tea dust glaze inside and flashing slip outside

8.5 x 7 x 3 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Pitcher, 2021

Wood fired stoneware pitcher with tea dust glaze inside and shino flashing slip outside

8.5 x 6.75 x 3 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Pitcher, 2021

Wood fired stoneware pitcher with tea dust glaze inside and white flashing slip outside

8.5 x 7 x 3.5 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Pitcher, 2021

Wood fired marbleized stoneware pitcher with tea dust glaze inside and flashing slip outside

9 x 6.5 x 3 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Footed Pitcher, 2021

Wood fired black stoneware footed pitcher with tea dust glaze inside and out

7.5 x 6.5 x 4 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Fluted Pitcher, 2021

Wood fired black stoneware fluted pitcher with tea dust glaze inside and out

9 x 7.5 x 4 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Pitcher, 2021

Wood fired black stoneware pitcher with tenmoku glaze inside and out

9 x 6 x 4.5 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Pitcher, 2021

Wood fired black stoneware pitcher with tea dust glaze inside and out

9.5 x 6.5 x 5.5 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Pitcher, 2021

Wood fired black stoneware pitcher with tenmoku and nuka glaze inside and out

8.5 x 7.2 x 4.75 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.

Photo by Frances Palmer

Stoneware Fluted Pitcher, 2021

Wood fired black stoneware fluted pitcher with tea dust glaze inside and out

10 x 7.5 x 4.5 inches

Frances Palmer (b. 1956, Morristown, NJ, USA) has been thinking about Giorgio Morandi lately. And well she might. For her art, like that of the great Italian painter, is an art of placement — of getting things just right, not just the things themselves, but the intervals between them as well. The vessel forms she has been making are fired in a wood kiln and sheathed in shimmering Chinese-style glazes. To the knowing eye they betray Palmer’s deep technical expertise. And yet, at the same time, they could almost have been plucked, by her magical fingers, from Morandi’s canvases — an impression reinforced by her use of them to hold branches and blooms from the Stone Barns farm. It’s a humble enough gesture, pitchers with flowers in them. But in Palmer’s hands, that commonplace conjunction becomes artful performance. Still life tradition itself seems to take a bow, crowned with laurels. A little victory for what matters most.