At The Luss House:

Blum & Poe, Mendes Wood DM and Object & Thing

May 7-July 24, 2021

Ossining, NY

Photo by Michael Biondo

Use left/right arrows to navigate the slideshow or swipe left/right if using a mobile device

Object & Thing joined international contemporary art galleries, Blum & Poe and Mendes Wood DM, in presenting an exhibition of newly created contemporary art and design, including site-specific works, at the former home of architect and designer Gerald Luss (b. 1926, Gloversville, NY) that he designed and completed for his family in 1955 in Ossining, New York. On view from May 7 - July 24, 2021, At The Luss House continued to explore the possibilities of connecting today’s artistic ideas with those of past eras through the presentation of contemporary art and design within an architect’s own domestic environment as the organizers also did at the home of industrial designer and Harvard Five architect, Eliot Noyes.

An influential designer and architect, Luss is best known for his influence on large-scale corporate projects during the post–World War II building boom in Manhattan, although his work can be found around the world. He is particularly noted for the innovations he developed for the 350,000 square feet of interiors for the famed Time-Life Building (1959) on Avenue of the Americas in midtown Manhattan – the epitome of midcentury modern skyscraper design, commonly recognized today as the backdrop to AMC’s Mad Men series. His home in Ossining, commuting distance from New York City, was Luss’s first freestanding architectural project and where he lived during the three years he spent working on the Time-Life project. The home was used for many planning meetings between Luss and Time-Life staff and employs a similar connection between interior and exterior environments as well as shared materials and color schemes. At 94 years old, Luss was a collaborative partner in

the exhibition by having lent examples of his furniture and designs.

In addition to the organizing galleries, Object & Thing presented works

contributed by Alison Bradley Projects (New York City) and GALLERY crossing (Minokamo, Japan).

Visit Blum & Poe's website here.

Visit Mendes Wood DM's website here.

For any questions related to the exhibition, please be in touch at lusshouse@object-thing.com.

With special thanks to Glenn Adamson, Emily Bode, Rafael de Cárdenas, Maureen Flaherty, Susan and Gerald Luss and Rick Rodgers

Exhibition video and installation photography by Michael Biondo

All images courtesy of the artists and:

Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo

Mendes Wood DM, São Paulo/Brussels/New York

Object & Thing, New York

Visitor Information

The Gerald Luss House is a private residence within a residential neighborhood in Ossining, New York, about thirty-five miles from New York City. The house is conveniently accessible by Metro-North Hudson Line to Croton-on-Hudson. It is then a ten minute drive from the station.

Due to a high level of interest, we are no longer able to add to the waitlist for visits to At The Luss House. For questions related to an existing reservation, please be in touch at lusshouse@object-thing.com.

- • In-person visits are available on Fridays and Saturdays from 10 am–6 pm through July 24.

- • Each visit begins at the start of the hour and lasts up to 45 minutes.

- • Appointments can include up to ten guests and a maximum of four parked vehicles.

- • There is no fee to visit.

- • Children are welcome when accompanied by an adult.

- • We are unable to welcome pets, unless a service animal.

- • All visitors are required to provide and wear face coverings when indoors.

- • Photography is permissible, for personal use.

- • Address details will be provided with a confirmed reservation. Please keep this information confidential for you and your guests.

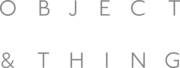

Installation Views

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Photo by Michael Biondo

Video Tour

Virtual Visit

Time, Life and Architecture

Sitting there, on a brilliant April morning, with Gerald Luss — on a luxuriant and expansive sofa he himself had designed, surrounded by artworks, with a breathtaking span of nature before us, visible through enormous steel-framed glass windows, hearing him talk about this surpassingly beautiful house which he had built to live in way back in the 1950s — a thought came to me. This is when everything made sense.

In all my experience as a design historian, I had never had that reaction to anyone or anything. Certainly not to modernism, which for someone of my generation feels like the baseline against which subsequent creativity has defined itself. It is the immovable canon. But for Luss — who was born in 1926 — it is quite different. For him, modernism was the great challenge, a brand-new experiment. To speak with him about form, space, detail and materials is to experience anew the unprecedented thrill of total clarity. Inarguable rightness. Actual perfection, here on earth.

Luss embraced that vision early in life, and has never wavered. When he was just a boy, growing up in what he describes as the thoroughly mediocre town of Gloversville, New York, he encountered the word architect. He thought immediately, “that’s what I want to be.”1 And so he did, studying at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and Pratt Institute immediately after the war. Upon graduating in 1948, he took up work at the firm Designs for Business, Inc., founded two years prior, which specialized in commercial interiors. His talent must have been abundantly obvious, for despite his youth, he was quickly appointed the firm’s chief designer.

Press consistently referred to him as the wunderkind of modern architecture in America. If Luss did not become a household name like his contemporaries Ray and Charles Eames or Eero Saarinen, that is partly due to his personal modesty — “an architect should build for the client, not for himself,” he says — but also because his chosen specialism was quite literally behind the scenes, and also temporary: the commercial offices he designed in the 1950s and 1960s no longer exist today. Yet it’s hard to believe that anyone in America designed more modern interiors than he did. The commissions that he completed for companies like Olin Mathieson and Owens-Corning measured in the hundreds of thousands of square feet, typically across multiple floors of a high-rise.2

The best known of these projects today is his work for the Time-Life Building in 1959. This sleek skyscraper, designed by Wallace Harrison under the immediate influence of Mies van der Rohe’s nearby Seagram Building, was the perfect setting for Luss’s inventive approach to interiors. In what he described as his Plenum system, all available space was conceived in a modular fashion, with each module incorporating the support elements of electricity, illumination, acoustics and sprinklers for fire control. Articulation of each floor was achieved using customized partitions with specially-designed “compressible joints,” which Luss would go on to patent.3 This allowed for the rapid conversion of spaces according to the needs of the moment. It was perfect for a large magazine company like Time-Life, with teams of people rapidly reconstituting their workspace needs in support of press deadlines.

To be sure, the working environments that Luss helped to shape had certain aspects that seem dated, today. Interiors praised his work for its “strong, masculine, and businesslike” feel: “the boss can lean back with heels on the desk and flick his cigar without feeling out of place.”4 That period atmosphere, with its combination of modernist glamour and pre-feminist gender dynamics, is perfectly captured in the hit AMC TV series Mad Men, which used the Time-Life Building as its setting for several seasons (partly shot on location, partly on intricately reconstructed sets out in Los Angeles). But Luss himself was a totally anti-hierarchical and humanistic thinker. The whole point of his modular system was to achieve “flexibility through inflexibility,” allowing each inhabitant of his spaces, no matter their role, to shape their own environment.

This same principle lies at the heart of Luss’s Ossining house, completed in 1955, when he was only twenty-nine (At that age, I believe, the extent of my own home furnishing ambitions was trying to get a ride to the nearest IKEA). Bursting with the confidence of youth, he first constructed a small elevated shelter in the trees, building it with Unistrut and outfitting it with a small solar panel to heat water. A shower was positioned under the sleeping platform. He lived there, a modern pioneer, for nine months while his house went through its gestation. Every morning and evening, he checked in with the builders to ensure that all details were executed according to his precise drawings: “I didn’t welcome the general contractor, or the plumber and electrician, to be on the design team.”

The result, it bears repeating, is perfect in every respect. The house is the quintessence of deceptive simplicity. Every element is considered, down to the 1/64th of an inch. Prefabricated industrial elements in self-weathering COR-TEN steel (a new material at the time) and timber combine with handcrafted cedar, cherry, cypress, Douglas Fir and walnut. The overall structure is held in tension, so that it “rings like a tyne when struck.”5 An oculus above the central stair lets in a circle of light, which traverses the paneled walls, making the house into a sundial timepiece. It is all quietly spectacular, yet also strangely self-effacing, yielding itself calmly to active inhabitation and to the cinematic glory of the woodland just beyond the glass. Executives from Time-Life loved the house, and often visited during the development of their offices; meetings were held around a ping-pong table on the lower level.

Luss ended up living there only a few years, perhaps because his family, with three children, rapidly outgrew the premises (though Interiors wondered about that; of his decision to build a new house, in King’s Point, they noted, “one suspects a hidden motive triggered by sheer creative drive.”).6 Eventually, he also moved on from Designs for Business, Inc., after sixteen years, setting up his own firm Luss/Kaplan and Associates. His aesthetic changed with the times, venturing into new palettes of color and material in keeping with the Pop aesthetic of the 1960s and 1970s; but his uncompromising individualism remained. He is still completing design commissions today, at the age of 94.

The house in Ossining also remains, of course, much as Luss envisioned it. The one major subsequent addition was built following his own plans for a possible extension.7 It also remains quietly radical in its implications about time, life and architecture: as Luss says, “with few exceptions most people historically have lived in and still live their lives within boxes, Ossining was the antithesis in that it was premised on the absence of unnecessary enclosures akin to what nature exhibits and endows.” Almost needless to say, it is also an ideal setting for art and design, notably including some of Luss’s own furniture — that gorgeous long sofa we sat on, and a coffee table, date to the period of the house’s original construction — and some of the immaculately designed clocks he has made over recent decades, an investigation of time as a world-wide common denominator, paralleling his interest in space as the most important concern for an architect.

The clocks are here as part of an installation organized by Object & Thing and contemporary art galleries, Blum & Poe and Mendes Wood DM. Following a similar (and equally ravishing) presentation at the house of Eliot Noyes in New Canaan, Connecticut, they have collaborated to fill the home and grounds with paintings, sculptures and functional objects. The selection is thoughtful in the extreme, somehow managing to match the exalted caliber of this architectural context. The general tendency is toward abstraction amplified by intense craftsmanship: each object radiates material intelligence.

I asked Luss what he thought about all these new works, placed into his seven-decade-old house, and he just smiled and said, “It’s never looked this good.” In that reaction, I had the sense of a man who has lived long and well. He’s seen a lot of history, while doing more than his share to shape and define it. He’s seen aesthetic directions come and go, some wildly at variance with his own sense of what’s right.8 I like to think that now, as we all try to extricate ourselves from a particularly turbulent time in history, we have come full circle. Via a wide-ranging postmodern transit, I hope that we’re able to appreciate the true value of creative minds like Gerald Luss, and what they have achieved. Looking around this idyllic place, an easel for the works of vibrant contemporaneity placed in it, a second thought occurs to me. Maybe everything does make sense today, after all.

By Glenn Adamson

1 Direct quotations from Gerald Luss are from an interview conducted on April 28, 2021.

2 Luss’s commission for Owens-Corning was a modern masterpiece, set in a glass skyscraper on Fifth Avenue and featuring a 60-foot-long Josef Albers mural, Eero Saarinen Tulip chairs, and Knoll fabrics. See Stuart Leslie, “The Strategy of Structure,” Enterprise & Society 12/4 (December 2011), 863-902.

3 “Partitioning System,” US Patent 3,189,140, June 15, 1965.

4 “Designs for Business, Inc.,” Interiors (January 1960), 84.

5 “Gerald Luss: The Designer Who Thinks of Everything,” Interiors (January 1957), 111.

6 “Paradise Found, or Nesting on the North Shore,” Interiors (January 1962), 75. Luss eventually moved again to a former opera house in Croton-on-Hudson. Tragically, that property suffered a serious fire in 2004, which destroyed the archives of his design work – another reason that this luminary of modern architecture has received less attention from historians than he is due.

7 The only substantial alterations to the property are the floor in the living area and bedroom, which was originally of 3 x 18-inch cork tiles, laid out in a herringbone pattern; and an extension of the bedroom hallway that added two bedrooms.

8 For some time, the primary metal support of the house was painted bright yellow by a subsequent owner. This has now been restored to the original restrained palette as an alternative preferred by Luss.

Artists

Lucas Arruda

Cecily Brown

Matt Connors

Green River Project LLC

Mimi Lauter

Tony Lewis

Eddie Martinez

Ritsue Mishima

Paulo Monteiro

Kiva Motnyk

Paulo Nazareth

Johnny Ortiz

Frances Palmer

Marina Perez Simão

Yoichi Shiraishi

Daniel Steegmann Mangrané

Kishio Suga

Selected Works Presented by Object & Thing

Photo by Andrew Jacobs

Green River Project LLC

Time-Life Building, 2021

Aluminum

29.5 x 80 x 36 inches

Green River Project LLC — the ever-inventive design and making studio of Aaron Aujla and Ben Bloomstein — is a frequent exhibitor with Object & Thing, bringing their bespoke approach to each presentation. For this installation, they met with Gerald Luss at his New York City home and studio, and created a response to his inspirational life and work. One rectangular table in aluminum — 122 pounds of it — is a response to the architecture of the Time-Life Building (1959), where Luss completed his most well-known interiors. The choice of aluminum, a commonality that ties all of Green River Project’s contributions to the exhibition, evokes the modernist yet lavish atmosphere of mid-century Manhattan (and it’s worth noting that it was only in those years that monumental construction in aluminum became commonplace). The pair of sconces included at Luss House were designed for the restaurant Dr. Clark in New York City.

Photo by Andrew Jacobs

Green River Project LLC

Aluminum Round Table, 2021

Aluminum

48 in diameter x 29.5 in height

Green River Project LLC — the ever-inventive design and making studio of Aaron Aujla and Ben Bloomstein — is a frequent exhibitor with Object & Thing, bringing their bespoke approach to each presentation. For this installation, they met with Gerald Luss at his New York City home and studio, and created a response to his inspirational life and work. One rectangular table in aluminum — 122 pounds of it — is a response to the architecture of the Time-Life Building (1959), where Luss completed his most well-known interiors. The choice of aluminum, a commonality that ties all of Green River Project’s contributions to the exhibition, evokes the modernist yet lavish atmosphere of mid-century Manhattan (and it’s worth noting that it was only in those years that monumental construction in aluminum became commonplace). The pair of sconces included at Luss House were designed for the restaurant Dr. Clark in New York City.

Photo by Andrew Jacobs

Green River Project LLC

Aluminum Chair, 2021

Aluminum

31.5 x 16.5 x 20 inches

Green River Project LLC — the ever-inventive design and making studio of Aaron Aujla and Ben Bloomstein — is a frequent exhibitor with Object & Thing, bringing their bespoke approach to each presentation. For this installation, they met with Gerald Luss at his New York City home and studio, and created a response to his inspirational life and work. One rectangular table in aluminum — 122 pounds of it — is a response to the architecture of the Time-Life Building (1959), where Luss completed his most well-known interiors. The choice of aluminum, a commonality that ties all of Green River Project’s contributions to the exhibition, evokes the modernist yet lavish atmosphere of mid-century Manhattan (and it’s worth noting that it was only in those years that monumental construction in aluminum became commonplace). The pair of sconces included at Luss House were designed for the restaurant Dr. Clark in New York City.

Photo by Andrew Jacobs

Green River Project LLC

Aluminum and Leather Lounge Chair, 2021

Aluminum, leather

25 x 31 x 48 inches

Green River Project LLC — the ever-inventive design and making studio of Aaron Aujla and Ben Bloomstein — is a frequent exhibitor with Object & Thing, bringing their bespoke approach to each presentation. For this installation, they met with Gerald Luss at his New York City home and studio, and created a response to his inspirational life and work. One rectangular table in aluminum — 122 pounds of it — is a response to the architecture of the Time-Life Building (1959), where Luss completed his most well-known interiors. The choice of aluminum, a commonality that ties all of Green River Project’s contributions to the exhibition, evokes the modernist yet lavish atmosphere of mid-century Manhattan (and it’s worth noting that it was only in those years that monumental construction in aluminum became commonplace). The pair of sconces included at Luss House were designed for the restaurant Dr. Clark in New York City.

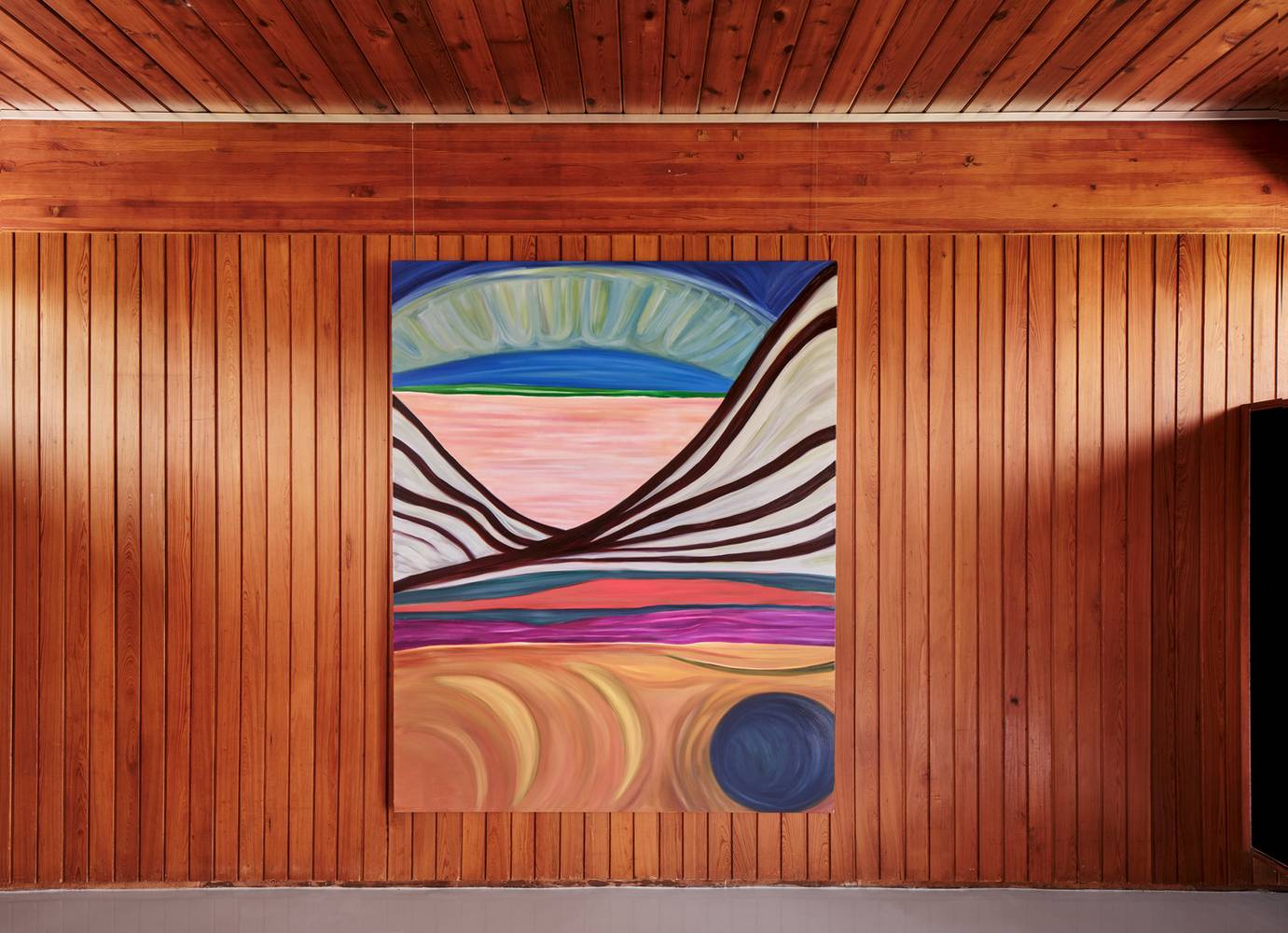

Photo by Andrew Jacobs

Green River Project LLC

Brushed Aluminum & Bamboo Sconce, 2021

Aluminum, bamboo

18 x 9.5 x 7 inches

Green River Project LLC — the ever-inventive design and making studio of Aaron Aujla and Ben Bloomstein — is a frequent exhibitor with Object & Thing, bringing their bespoke approach to each presentation. For this installation, they met with Gerald Luss at his New York City home and studio, and created a response to his inspirational life and work. One rectangular table in aluminum — 122 pounds of it — is a response to the architecture of the Time-Life Building (1959), where Luss completed his most well-known interiors. The choice of aluminum, a commonality that ties all of Green River Project’s contributions to the exhibition, evokes the modernist yet lavish atmosphere of mid-century Manhattan (and it’s worth noting that it was only in those years that monumental construction in aluminum became commonplace). The pair of sconces included at Luss House were designed for the restaurant Dr. Clark in New York City.

Photo by Matthew Chin

Kiva Motnyk

Afternoon Light - Multi, 2021

Framed piecework fabric panel made from French seamed silk, naturally dyed and hand-woven Korean pojagi silk, hand appliquéd North Indian silk, cotton velvet, Belgian linen, open weave linens, mixed hand-embroidery and naturally dyed remnants

95 x 65 inches

Since 2014, Kiva Motnyk has been the head of Thompson Street Studio, drawing on a background in high fashion to create textiles infused with natural dyes derived from foraged plants. Her pieces incorporate naturally dyed fabrics from her own dyes as well as collected antique linens, silks and mud cloths from around the world. (She has a particular love for textiles that already include collage elements, like Korean pojagi and Japanese boro.) Motnyk has created five new works for the presentation at The Gerald Luss House, including three tapestries placed over each of the bedrooms beds, a patchwork piece folded as a hand towel in the bathroom, and – most spectacular of all - the aptly titled Afternoon Light – Multi, a hand-pieced fabric panel stretched within a wooden frame that fills the main bedroom window. It infuses the space with the transcendent polychrome of medieval stained glass, while also establishing a sympathetic conversation with Gerald Luss’s gloriously externalized modernist architecture.

Photo by Matthew Chin

Kiva Motnyk

Botanic Study - Indigo, 2021

Tapestry made from pieced Belgian linen, silks, antique Japanese boro and African mud cloth, naturally dyed indigo textiles and mixed antique remnants with 100% organic cotton batting

112 x 92 inches

Since 2014, Kiva Motnyk has been the head of Thompson Street Studio, drawing on a background in high fashion to create textiles infused with natural dyes derived from foraged plants. Her pieces incorporate naturally dyed fabrics from her own dyes as well as collected antique linens, silks and mud cloths from around the world. (She has a particular love for textiles that already include collage elements, like Korean pojagi and Japanese boro.) Motnyk has created five new works for the presentation at The Gerald Luss House, including three tapestries placed over each of the bedrooms beds, a patchwork piece folded as a hand towel in the bathroom, and – most spectacular of all - the aptly titled Afternoon Light – Multi, a hand-pieced fabric panel stretched within a wooden frame that fills the main bedroom window. It infuses the space with the transcendent polychrome of medieval stained glass, while also establishing a sympathetic conversation with Gerald Luss’s gloriously externalized modernist architecture.

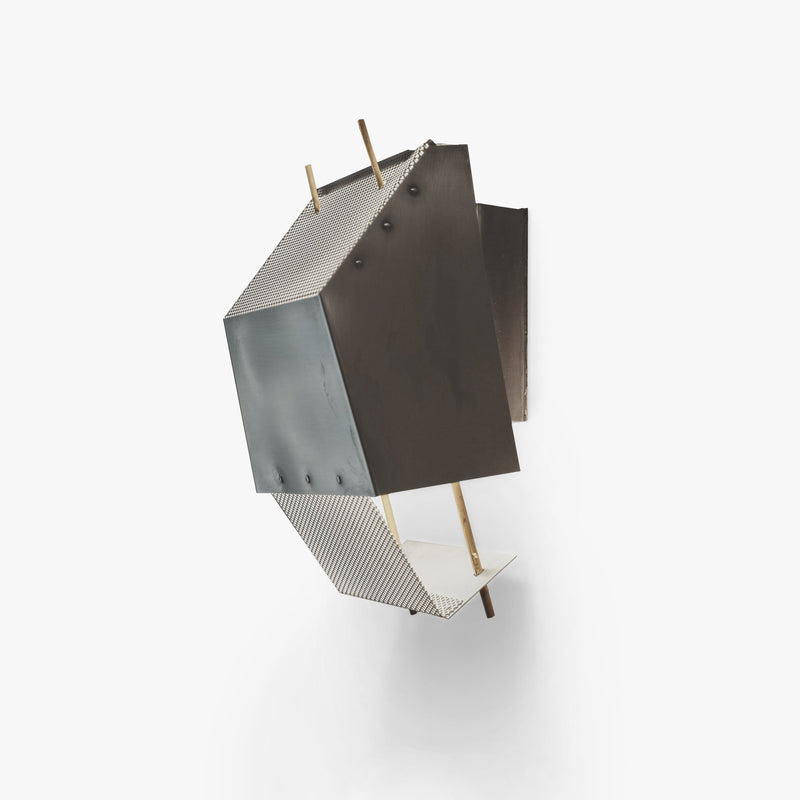

Photo by Matthew Chin

Kiva Motnyk

Pastoral Landscape - Soft Neutrals, 2021

Tapestry made from pieced Belgian linen, antique and contemporary silk, African mud cloth, hand-loomed and embroidered north Indian tapestries mixed with novelty French interiors fabric and hand-woven Korean silks with

100% Belgian linen backing

92 x 92 inches

Since 2014, Kiva Motnyk has been the head of Thompson Street Studio, drawing on a background in high fashion to create textiles infused with natural dyes derived from foraged plants. Her pieces incorporate naturally dyed fabrics from her own dyes as well as collected antique linens, silks and mud cloths from around the world. (She has a particular love for textiles that already include collage elements, like Korean pojagi and Japanese boro.) Motnyk has created five new works for the presentation at The Gerald Luss House, including three tapestries placed over each of the bedrooms beds, a patchwork piece folded as a hand towel in the bathroom, and – most spectacular of all - the aptly titled Afternoon Light – Multi, a hand-pieced fabric panel stretched within a wooden frame that fills the main bedroom window. It infuses the space with the transcendent polychrome of medieval stained glass, while also establishing a sympathetic conversation with Gerald Luss’s gloriously externalized modernist architecture.

Photo by Matthew Chin

Kiva Motnyk

Line Tapestry - Neutral, 2021

Tapestry made from seamed antique Italian silk, Belgian linen, appliquéd north Indian silk, African mud cloth, hand embroidered north Indian silk, antique Japanese printed silk, naturally dyed mixed remnants and Korean hand-woven and dyed silk

92 x 86 inches

Since 2014, Kiva Motnyk has been the head of Thompson Street Studio, drawing on a background in high fashion to create textiles infused with natural dyes derived from foraged plants. Her pieces incorporate naturally dyed fabrics from her own dyes as well as collected antique linens, silks and mud cloths from around the world. (She has a particular love for textiles that already include collage elements, like Korean pojagi and Japanese boro.) Motnyk has created five new works for the presentation at The Gerald Luss House, including three tapestries placed over each of the bedrooms beds, a patchwork piece folded as a hand towel in the bathroom, and – most spectacular of all - the aptly titled Afternoon Light – Multi, a hand-pieced fabric panel stretched within a wooden frame that fills the main bedroom window. It infuses the space with the transcendent polychrome of medieval stained glass, while also establishing a sympathetic conversation with Gerald Luss’s gloriously externalized modernist architecture.

Photo by Matthew Chin

Kiva Motnyk

Tea Towel - Multi, 2021

Tea towel made from Belgian linen, silk, antique Japanese indigo botanics, African mud cloth and open weave yarn dyed linen and cotton velvet

50.5 x 21 inches

Since 2014, Kiva Motnyk has been the head of Thompson Street Studio, drawing on a background in high fashion to create textiles infused with natural dyes derived from foraged plants. Her pieces incorporate naturally dyed fabrics from her own dyes as well as collected antique linens, silks and mud cloths from around the world. (She has a particular love for textiles that already include collage elements, like Korean pojagi and Japanese boro.) Motnyk has created five new works for the presentation at The Gerald Luss House, including three tapestries placed over each of the bedrooms beds, a patchwork piece folded as a hand towel in the bathroom, and – most spectacular of all - the aptly titled Afternoon Light – Multi, a hand-pieced fabric panel stretched within a wooden frame that fills the main bedroom window. It infuses the space with the transcendent polychrome of medieval stained glass, while also establishing a sympathetic conversation with Gerald Luss’s gloriously externalized modernist architecture.

Photo by Maida Branch and Johnny Ortiz

Johnny Ortiz

Shallow Vessel 1, 2021

Micaceous earth from Northern New Mexico, sanded with local sandstone, burnished with a river stone, pit fired with red cedar during the February 2021 Snow Moon and cured with elk marrow and beeswax

15 in diameter x 2.75 in height

Artist and chef Johnny Ortiz digs deep in his work — literally. His primary ceramic material is micaceous “wild clay,” harvested in his home state of New Mexico. The micaceous clay he uses is from the same terrain his ancestors, Taos pueblo, have dug for hundreds if not thousands of years. When he first re-discovered this resource, his first instinct was to leave it in the ground: it seemed, he says, “too stunning to do anything with.” But he gradually came to grips with it, seeing in the clay a means of connecting to his own ancestral past, as well as to present-day aesthetic possibilities. He makes the material his own through an elaborate series of procedures, first sanding the pots with rough sandstone and then burnishing with smoother river stone, pit firing them with red mountain cedar he gathered from the mountains he inhabits, and finally, “curing” them with elk marrow and beeswax. This presentation at The Gerald Luss House, undertaken on the heels of Ortiz’s stint as a guest chef in the nearby Stone Barns Center and Blue Hill residency program, includes vessels fired during the 2021 Snow Moon.

Photo by Maida Branch and Johnny Ortiz

Johnny Ortiz

Vessel 1, 2021

Micaceous earth from Northern New Mexico, sanded with local sandstone, burnished with a river stone, pit fired with red cedar during the February 2021 Snow Moon and cured with elk marrow and beeswax

11 in diameter x 3.125 in height

Artist and chef Johnny Ortiz digs deep in his work — literally. His primary ceramic material is micaceous “wild clay,” harvested in his home state of New Mexico. The micaceous clay he uses is from the same terrain his ancestors, Taos pueblo, have dug for hundreds if not thousands of years. When he first re-discovered this resource, his first instinct was to leave it in the ground: it seemed, he says, “too stunning to do anything with.” But he gradually came to grips with it, seeing in the clay a means of connecting to his own ancestral past, as well as to present-day aesthetic possibilities. He makes the material his own through an elaborate series of procedures, first sanding the pots with rough sandstone and then burnishing with smoother river stone, pit firing them with red mountain cedar he gathered from the mountains he inhabits, and finally, “curing” them with elk marrow and beeswax. This presentation at The Gerald Luss House, undertaken on the heels of Ortiz’s stint as a guest chef in the nearby Stone Barns Center and Blue Hill residency program, includes vessels fired during the 2021 Snow Moon.

Photo by Maida Branch and Johnny Ortiz

Johnny Ortiz

Bean Pot, 2021

Micaceous earth from Northern New Mexico, sanded with local sandstone, burnished with a river stone, pit fired with red cedar during the February 2021 Snow Moon and cured with elk marrow and beeswax

9 in diameter x 5.5 in height

Artist and chef Johnny Ortiz digs deep in his work – literally. His primary ceramic material is micaceous “wild clay,” found in his home state of New Mexico. When he first discovered this resource, his first instinct was to leave it in the ground: it seemed, he says, “too stunning to do anything with.” But he gradually came to grips with it, seeing in the clay a means of connecting to his own ancestral past, as well as to present-day aesthetic possibilities. He makes the material his own through an elaborate series of procedures, first burnishing the pots with rough sandstone and then smoother river stone, pit firing them with red mountain cedar, and finally, “curing” them with elk marrow and beeswax. This presentation at The Gerald Luss House, undertaken on the heels of Ortiz’s stint as a guest chef in the nearby Stone Barns Center and Blue Hill residency program, includes vessels fired during the 2021 Snow Moon.

Photo by Maida Branch and Johnny Ortiz

Johnny Ortiz

Shallow Vessel 2, 2021

Micaceous earth from Northern New Mexico, sanded with local sandstone, burnished with a river stone, pit fired with red cedar during the February 2021 Snow Moon and cured with elk marrow and beeswax

12 in diameter x 2.25 in height

Artist and chef Johnny Ortiz digs deep in his work — literally. His primary ceramic material is micaceous “wild clay,” harvested in his home state of New Mexico. The micaceous clay he uses is from the same terrain his ancestors, Taos pueblo, have dug for hundreds if not thousands of years. When he first re-discovered this resource, his first instinct was to leave it in the ground: it seemed, he says, “too stunning to do anything with.” But he gradually came to grips with it, seeing in the clay a means of connecting to his own ancestral past, as well as to present-day aesthetic possibilities. He makes the material his own through an elaborate series of procedures, first sanding the pots with rough sandstone and then burnishing with smoother river stone, pit firing them with red mountain cedar he gathered from the mountains he inhabits, and finally, “curing” them with elk marrow and beeswax. This presentation at The Gerald Luss House, undertaken on the heels of Ortiz’s stint as a guest chef in the nearby Stone Barns Center and Blue Hill residency program, includes vessels fired during the 2021 Snow Moon.

Photo by Maida Branch and Johnny Ortiz

Johnny Ortiz

Shallow Vessel 3, 2021

Micaceous earth from Northern New Mexico, sanded with local sandstone, burnished with a river stone, pit fired with red cedar during the February 2021 Snow Moon and cured with elk marrow and beeswax

10 in diameter x 1.75 in height

Artist and chef Johnny Ortiz digs deep in his work — literally. His primary ceramic material is micaceous “wild clay,” harvested in his home state of New Mexico. The micaceous clay he uses is from the same terrain his ancestors, Taos pueblo, have dug for hundreds if not thousands of years. When he first re-discovered this resource, his first instinct was to leave it in the ground: it seemed, he says, “too stunning to do anything with.” But he gradually came to grips with it, seeing in the clay a means of connecting to his own ancestral past, as well as to present-day aesthetic possibilities. He makes the material his own through an elaborate series of procedures, first sanding the pots with rough sandstone and then burnishing with smoother river stone, pit firing them with red mountain cedar he gathered from the mountains he inhabits, and finally, “curing” them with elk marrow and beeswax. This presentation at The Gerald Luss House, undertaken on the heels of Ortiz’s stint as a guest chef in the nearby Stone Barns Center and Blue Hill residency program, includes vessels fired during the 2021 Snow Moon.

Photo by Maida Branch and Johnny Ortiz

Johnny Ortiz

Petal Bowl 1, 2021

Micaceous earth from Northern New Mexico, sanded with local sandstone, burnished with a river stone, pit fired with red cedar during the February 2021 Snow Moon and cured with elk marrow and beeswax

8.5 in diameter x 1.25 in height

Artist and chef Johnny Ortiz digs deep in his work — literally. His primary ceramic material is micaceous “wild clay,” harvested in his home state of New Mexico. The micaceous clay he uses is from the same terrain his ancestors, Taos pueblo, have dug for hundreds if not thousands of years. When he first re-discovered this resource, his first instinct was to leave it in the ground: it seemed, he says, “too stunning to do anything with.” But he gradually came to grips with it, seeing in the clay a means of connecting to his own ancestral past, as well as to present-day aesthetic possibilities. He makes the material his own through an elaborate series of procedures, first sanding the pots with rough sandstone and then burnishing with smoother river stone, pit firing them with red mountain cedar he gathered from the mountains he inhabits, and finally, “curing” them with elk marrow and beeswax. This presentation at The Gerald Luss House, undertaken on the heels of Ortiz’s stint as a guest chef in the nearby Stone Barns Center and Blue Hill residency program, includes vessels fired during the 2021 Snow Moon.

Photo by Maida Branch and Johnny Ortiz

Johnny Ortiz

Vessel 2, 2021

Micaceous earth from Northern New Mexico, sanded with local sandstone, burnished with a river stone, pit fired with red cedar during the February 2021 Snow Moon and cured with elk marrow and beeswax

5.5 in diameter x 2.5 in height

Artist and chef Johnny Ortiz digs deep in his work — literally. His primary ceramic material is micaceous “wild clay,” harvested in his home state of New Mexico. The micaceous clay he uses is from the same terrain his ancestors, Taos pueblo, have dug for hundreds if not thousands of years. When he first re-discovered this resource, his first instinct was to leave it in the ground: it seemed, he says, “too stunning to do anything with.” But he gradually came to grips with it, seeing in the clay a means of connecting to his own ancestral past, as well as to present-day aesthetic possibilities. He makes the material his own through an elaborate series of procedures, first sanding the pots with rough sandstone and then burnishing with smoother river stone, pit firing them with red mountain cedar he gathered from the mountains he inhabits, and finally, “curing” them with elk marrow and beeswax. This presentation at The Gerald Luss House, undertaken on the heels of Ortiz’s stint as a guest chef in the nearby Stone Barns Center and Blue Hill residency program, includes vessels fired during the 2021 Snow Moon.

Photo by Maida Branch and Johnny Ortiz

Johnny Ortiz

Vessel 4, 2021

Micaceous earth from Northern New Mexico, sanded with local sandstone, burnished with a river stone, pit fired with red cedar during the February 2021 Snow Moon and cured with elk marrow and beeswax

3 in diameter x 3.25 in height

Artist and chef Johnny Ortiz digs deep in his work — literally. His primary ceramic material is micaceous “wild clay,” harvested in his home state of New Mexico. The micaceous clay he uses is from the same terrain his ancestors, Taos pueblo, have dug for hundreds if not thousands of years. When he first re-discovered this resource, his first instinct was to leave it in the ground: it seemed, he says, “too stunning to do anything with.” But he gradually came to grips with it, seeing in the clay a means of connecting to his own ancestral past, as well as to present-day aesthetic possibilities. He makes the material his own through an elaborate series of procedures, first sanding the pots with rough sandstone and then burnishing with smoother river stone, pit firing them with red mountain cedar he gathered from the mountains he inhabits, and finally, “curing” them with elk marrow and beeswax. This presentation at The Gerald Luss House, undertaken on the heels of Ortiz’s stint as a guest chef in the nearby Stone Barns Center and Blue Hill residency program, includes vessels fired during the 2021 Snow Moon.

Photo by Maida Branch and Johnny Ortiz

Johnny Ortiz

Plate 1, 2021

Micaceous earth from Northern New Mexico, sanded with local sandstone, burnished with a river stone, pit fired with red cedar during the February 2021 Snow Moon and cured with elk marrow and beeswax

10.25 in diameter x .5 in height

Artist and chef Johnny Ortiz digs deep in his work — literally. His primary ceramic material is micaceous “wild clay,” harvested in his home state of New Mexico. The micaceous clay he uses is from the same terrain his ancestors, Taos pueblo, have dug for hundreds if not thousands of years. When he first re-discovered this resource, his first instinct was to leave it in the ground: it seemed, he says, “too stunning to do anything with.” But he gradually came to grips with it, seeing in the clay a means of connecting to his own ancestral past, as well as to present-day aesthetic possibilities. He makes the material his own through an elaborate series of procedures, first sanding the pots with rough sandstone and then burnishing with smoother river stone, pit firing them with red mountain cedar he gathered from the mountains he inhabits, and finally, “curing” them with elk marrow and beeswax. This presentation at The Gerald Luss House, undertaken on the heels of Ortiz’s stint as a guest chef in the nearby Stone Barns Center and Blue Hill residency program, includes vessels fired during the 2021 Snow Moon.

Photo by Maida Branch and Johnny Ortiz

Johnny Ortiz

Plate 2, 2021

Micaceous earth from Northern New Mexico, sanded with local sandstone, burnished with a river stone, pit fired with red cedar during the February 2021 Snow Moon and cured with elk marrow and beeswax

7.5 in diameter x .25 in height

Artist and chef Johnny Ortiz digs deep in his work — literally. His primary ceramic material is micaceous “wild clay,” harvested in his home state of New Mexico. The micaceous clay he uses is from the same terrain his ancestors, Taos pueblo, have dug for hundreds if not thousands of years. When he first re-discovered this resource, his first instinct was to leave it in the ground: it seemed, he says, “too stunning to do anything with.” But he gradually came to grips with it, seeing in the clay a means of connecting to his own ancestral past, as well as to present-day aesthetic possibilities. He makes the material his own through an elaborate series of procedures, first sanding the pots with rough sandstone and then burnishing with smoother river stone, pit firing them with red mountain cedar he gathered from the mountains he inhabits, and finally, “curing” them with elk marrow and beeswax. This presentation at The Gerald Luss House, undertaken on the heels of Ortiz’s stint as a guest chef in the nearby Stone Barns Center and Blue Hill residency program, includes vessels fired during the 2021 Snow Moon.

Photo by Maida Branch and Johnny Ortiz

Johnny Ortiz

Petal Bowl 2, 2021

Micaceous earth from Northern New Mexico, sanded with local sandstone, burnished with a river stone, pit fired with red cedar during the February 2021 Snow Moon and cured with elk marrow and beeswax

7 in diameter x .25 in height

Artist and chef Johnny Ortiz digs deep in his work — literally. His primary ceramic material is micaceous “wild clay,” harvested in his home state of New Mexico. The micaceous clay he uses is from the same terrain his ancestors, Taos pueblo, have dug for hundreds if not thousands of years. When he first re-discovered this resource, his first instinct was to leave it in the ground: it seemed, he says, “too stunning to do anything with.” But he gradually came to grips with it, seeing in the clay a means of connecting to his own ancestral past, as well as to present-day aesthetic possibilities. He makes the material his own through an elaborate series of procedures, first sanding the pots with rough sandstone and then burnishing with smoother river stone, pit firing them with red mountain cedar he gathered from the mountains he inhabits, and finally, “curing” them with elk marrow and beeswax. This presentation at The Gerald Luss House, undertaken on the heels of Ortiz’s stint as a guest chef in the nearby Stone Barns Center and Blue Hill residency program, includes vessels fired during the 2021 Snow Moon.

Photo by Maida Branch and Johnny Ortiz

Johnny Ortiz

Plate 3, 2021

Micaceous earth from Northern New Mexico, sanded with local sandstone, burnished with a river stone, pit fired with red cedar during the February 2021 Snow Moon and cured with elk marrow and beeswax

5.75 in diameter x .25 in height

Artist and chef Johnny Ortiz digs deep in his work — literally. His primary ceramic material is micaceous “wild clay,” harvested in his home state of New Mexico. The micaceous clay he uses is from the same terrain his ancestors, Taos pueblo, have dug for hundreds if not thousands of years. When he first re-discovered this resource, his first instinct was to leave it in the ground: it seemed, he says, “too stunning to do anything with.” But he gradually came to grips with it, seeing in the clay a means of connecting to his own ancestral past, as well as to present-day aesthetic possibilities. He makes the material his own through an elaborate series of procedures, first sanding the pots with rough sandstone and then burnishing with smoother river stone, pit firing them with red mountain cedar he gathered from the mountains he inhabits, and finally, “curing” them with elk marrow and beeswax. This presentation at The Gerald Luss House, undertaken on the heels of Ortiz’s stint as a guest chef in the nearby Stone Barns Center and Blue Hill residency program, includes vessels fired during the 2021 Snow Moon.

Photo by Maida Branch and Johnny Ortiz

Johnny Ortiz

Rose Bowl, 2021

Micaceous earth from Northern New Mexico, sanded with local sandstone, burnished with a river stone, pit fired with red cedar during the February 2021 Snow Moon and cured with elk marrow and beeswax

5.25 in diameter x .75 in height

Artist and chef Johnny Ortiz digs deep in his work — literally. His primary ceramic material is micaceous “wild clay,” harvested in his home state of New Mexico. The micaceous clay he uses is from the same terrain his ancestors, Taos pueblo, have dug for hundreds if not thousands of years. When he first re-discovered this resource, his first instinct was to leave it in the ground: it seemed, he says, “too stunning to do anything with.” But he gradually came to grips with it, seeing in the clay a means of connecting to his own ancestral past, as well as to present-day aesthetic possibilities. He makes the material his own through an elaborate series of procedures, first sanding the pots with rough sandstone and then burnishing with smoother river stone, pit firing them with red mountain cedar he gathered from the mountains he inhabits, and finally, “curing” them with elk marrow and beeswax. This presentation at The Gerald Luss House, undertaken on the heels of Ortiz’s stint as a guest chef in the nearby Stone Barns Center and Blue Hill residency program, includes vessels fired during the 2021 Snow Moon.

Photo by Maida Branch and Johnny Ortiz

Johnny Ortiz

Palm Plate 1, 2021

Micaceous earth from Northern New Mexico, sanded with local sandstone, burnished with a river stone, pit fired with red cedar during the February 2021 Snow Moon and cured with elk marrow and beeswax

4.5 in diameter x .25 in height

Artist and chef Johnny Ortiz digs deep in his work — literally. His primary ceramic material is micaceous “wild clay,” harvested in his home state of New Mexico. The micaceous clay he uses is from the same terrain his ancestors, Taos pueblo, have dug for hundreds if not thousands of years. When he first re-discovered this resource, his first instinct was to leave it in the ground: it seemed, he says, “too stunning to do anything with.” But he gradually came to grips with it, seeing in the clay a means of connecting to his own ancestral past, as well as to present-day aesthetic possibilities. He makes the material his own through an elaborate series of procedures, first sanding the pots with rough sandstone and then burnishing with smoother river stone, pit firing them with red mountain cedar he gathered from the mountains he inhabits, and finally, “curing” them with elk marrow and beeswax. This presentation at The Gerald Luss House, undertaken on the heels of Ortiz’s stint as a guest chef in the nearby Stone Barns Center and Blue Hill residency program, includes vessels fired during the 2021 Snow Moon.

Photo by Maida Branch and Johnny Ortiz

Johnny Ortiz

Palm Plate 2, 2021

Micaceous earth from Northern New Mexico, sanded with local sandstone, burnished with a river stone, pit fired with red cedar during the February 2021 Snow Moon and cured with elk marrow and beeswax

3.5 in diameter x .125 in height

Artist and chef Johnny Ortiz digs deep in his work — literally. His primary ceramic material is micaceous “wild clay,” harvested in his home state of New Mexico. The micaceous clay he uses is from the same terrain his ancestors, Taos pueblo, have dug for hundreds if not thousands of years. When he first re-discovered this resource, his first instinct was to leave it in the ground: it seemed, he says, “too stunning to do anything with.” But he gradually came to grips with it, seeing in the clay a means of connecting to his own ancestral past, as well as to present-day aesthetic possibilities. He makes the material his own through an elaborate series of procedures, first sanding the pots with rough sandstone and then burnishing with smoother river stone, pit firing them with red mountain cedar he gathered from the mountains he inhabits, and finally, “curing” them with elk marrow and beeswax. This presentation at The Gerald Luss House, undertaken on the heels of Ortiz’s stint as a guest chef in the nearby Stone Barns Center and Blue Hill residency program, includes vessels fired during the 2021 Snow Moon.

Photo by Maida Branch and Johnny Ortiz

Johnny Ortiz

Vessel 5, 2021

Micaceous earth from Northern New Mexico, sanded with local sandstone, burnished with a river stone, pit fired with red cedar during the February 2021 Snow Moon and cured with elk marrow and beeswax

3 in diameter x 1 in height

Artist and chef Johnny Ortiz digs deep in his work — literally. His primary ceramic material is micaceous “wild clay,” harvested in his home state of New Mexico. The micaceous clay he uses is from the same terrain his ancestors, Taos pueblo, have dug for hundreds if not thousands of years. When he first re-discovered this resource, his first instinct was to leave it in the ground: it seemed, he says, “too stunning to do anything with.” But he gradually came to grips with it, seeing in the clay a means of connecting to his own ancestral past, as well as to present-day aesthetic possibilities. He makes the material his own through an elaborate series of procedures, first sanding the pots with rough sandstone and then burnishing with smoother river stone, pit firing them with red mountain cedar he gathered from the mountains he inhabits, and finally, “curing” them with elk marrow and beeswax. This presentation at The Gerald Luss House, undertaken on the heels of Ortiz’s stint as a guest chef in the nearby Stone Barns Center and Blue Hill residency program, includes vessels fired during the 2021 Snow Moon.

Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

Ritsue Mishima

Seed Crystal, 2017

Glass

14.13 x 13.38 inches

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

Ritsue Mishima

Fonte, 2020

Glass

12.38 x 15.5 inches

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

Ritsue Mishima

Lemuria, 2018

Glass

17.13 x 15.13 inches

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

Ritsue Mishima

Jomon, 2020

Glass

19.25 x 16.75 inches

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

Ritsue Mishima

Jomon, 2020

Glass

19.88 x 15.5 inches

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

Ritsue Mishima

Po, 2016

Glass

16.75 x 11.75 inches

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

Ritsue Mishima

Ouvo di Neve, 2012

Glass

8.13 x 10.88 x 6.13 inches

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

Ritsue Mishima

Bobina, 2007

Glass

2.38 in diameter x 4 in height

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

Ritsue Mishima

Cuore, 2012

Glass

9.38 in diameter x 5.88 in height

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

Ritsue Mishima

Torre 1, 2007

Glass

3.38 in diameter x 3.38 in height

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

Ritsue Mishima

Bozzolo Di Seta, 2012

Glass

6.25 x 9.25 x 5.25 inches

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

Ritsue Mishima

Luce di Luna, 2007

Glass

2.5 in diameter x 3.13 in height

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

Ritsue Mishima

Grandine, 2012

Glass

2.75 in diameter x 3.13 in height

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

Ritsue Mishima

Suimon, 2007

Glass

7.63 in diameter x 10.13 in height

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

Ritsue Mishima

Suimon 2, 2007

Glass

2.5 in diameter x 2.5 in height

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

Ritsue Mishima

Fiore di Neve, 2007

Glass

6.88 in diameter x 6.88 in height

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

Ritsue Mishima

Suono di Acqua, 2007

Glass

2.75 in diameter x 2.13 in height

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

Ritsue Mishima

Suono, 2007

Glass

3.25 in diameter x 3.25 in height

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo courtesy of Shibunkaku

Ritsue Mishima

Anima, 2012

Glass

8.38 x 5.88 x 8.38 inches

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo by Francesco Barasciutti

Ritsue Mishima

Arca, 2012

Glass

5.75 inches

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

Ritsue Mishima

Stella Cadente 1, 2007

Glass

4.75 in diameter x 3.38 in height

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

Ritsue Mishima

Capsula di Luce 2, 2007

Glass

2.88 in diameter x 3.38 in height

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects

The Jōmon pots of ancient Japan are thought to be the oldest of all ceramics; and in some respects, over the course of millennia, they have never been surpassed. They are often crowned by complex structures that scholars liken to flames – though in fact, we have no idea what they are meant to convey. For the Japanese artist Ritsue Mishima, who works between Kyoto and the historic glass center of Murano, near Venice, the mysterious Jōmon wares are an unendingly rich source of inspiration. She inverts the material polarity of the historic pots, rendering the forms transparent, while retaining their muscular gestural quality and evocative abstraction. Her practice involves collaborating with the glassmiths of Murano and always working with clear glass. At The Gerald Luss House, the sculptures land with the impact of meteors. Yet they also find subtle resonances with the expansive glass walls of the house, and the natural environment beyond. Her assured and formally precise vessels for chanoyu (tea ceremony), rarely exhibited outside of Japan, are also placed throughout the house.

Photo by Yasushi Ichikawa

Ritsue Mishima

Koto, 2007

Glass

2.5 in diameter x 3.13 in height

Contributed by Alison Bradley Projects